A 53-year-old man from Germany, referred to as the Dusseldorf patient, has become at least the third person to have been “cured of HIV” with the virus not being detectable in his body even four years after stopping the medicine. This was achieved with a bone-marrow transplant from people carrying a specific HIV-resistant genetic mutation.

What is this genetic mutation and can it bring an end to HIV, once and for all?

Who are the people who have become HIV-free?

Referred to as the Berlin patient, Timothy Ray Brown became the first person to overcome HIV after he underwent two stem cell transplants in 2007 and 2008 for treating his blood cancer. As a person with HIV, his doctors selected a donor carrying two copies of a CCR5-delta 32 genetic mutation – a mutation that is known to make the carriers almost immune to HIV. He remained HIV free till his death due to the cancer in 2020.

Years later, researchers announced similar results in the London patient Adam Castillejo in 2019, replicating the treatment for the first time. The Dusseldorf patient, who also underwent a transplant for blood cancer, has remained free of HIV four years after he stopped taking antiretroviral that control the level of the virus in the body.

Two other cases of ‘The City of Hope patient’ and ‘New York patient’ were also reported in 2022. The transplant in the New York patient was done using a dual stem cell therapy – using stem cells from umbilical cord of a neonate, complemented with stem cells from an adult – that requires less restrictive HLA matching. This is important as it may help people from different races get transplant with CCR5-delta 32 mutation, which is naturally found mostly in Europeans.

What is CCR5 mutation and how does it fight off HIV?

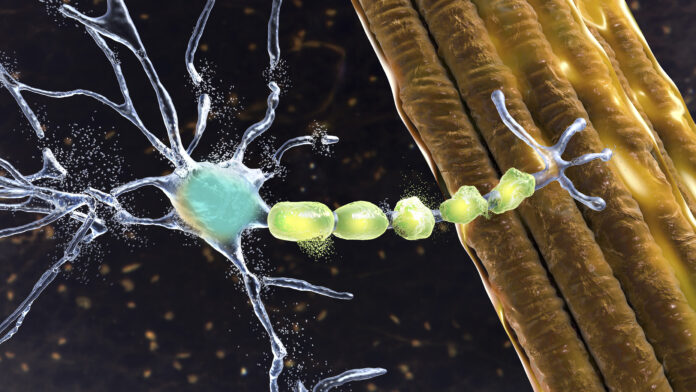

The HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) mainly attacks the CD4 immune cells in the human body, thereby reducing a person’s ability to fight off secondary infections. The CCR5 receptors on the surface of the CD4 immune cells act as doorway for the HIV virus. However, the CCR5-delta 32 mutation prevents these receptors used by the HIV virus from forming on the surface, effectively removing the doorway.

Only 1 per cent of the people in the world carry two copies of the CCR5-delta 32 mutation – meaning they got it from both their parents – and another 20 per cent carry one copy of the mutation, mainly those of European descent. Those with the mutation hence are almost immune to the infection, although some cases have been reported.

Can such transplants solve the HIV crisis?

With the mutation existing in very few people and nearly 38.4 million people living with HIV across the world, it would be very difficult to find a matching donor in the first place. Add to that the fact that the mutation occurs mainly among Caucasians, and the donor pool shrinks further for many, especially those from countries with high HIV burden.

However, even if donors were to become available, experts believe it is highly unlikely that bone marrow transplants can be rolled out for all those with HIV. This is because it is a major procedure with high risks associated, especially that of the person rejecting the donated marrow.

There is also the likelihood of the virus mutating to enter the cells through other mechanisms in such persons.

Why did the Chinese researcher who edited this gene out face backlash?

A Chinese scientist called He Jiankui in 2018 edited the genomes of twins Lulu and Nana to remove this CCR5 gene in an attempt to make them immune to HIV. Their father was living with HIV.

A month after the first babies were born in October 2018, he announced that he had created the first genetically edited babies. He faced immediate backlash from the scientific community and legal action. This is because guidelines for genetic editing prohibits germ-line editing – editing a genome that can be passed from one generation to the other – as the editing techniques are not very precise and long term consequences of such editing is unknown.

And, antiretroviral therapy could any way have prevented mother to child transmission of HIV.

What are the current treatments for HIV?

Although there are no cures for the infection at present, the disease can be managed using antiretroviral therapy. These medicines suppress the replication of the virus within the body, allowing the number of CD4 immune cells to bounce back. Although earlier the drugs were given only to those with low CD4 count under the government’s programme, now the programme supports anyone who has been diagnosed with HIV.

The drugs have to be taken for life because the virus continues to persist in reservoirs across the body. If the drugs are stopped, the virus can again start replicating and spreading. When the viral levels are low, the likelihood of a person transmitting the infection is also low.

If left untreated, the virus destroys a person’s immune system and they are said to be in Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome stage (AIDS) where they get several opportunistic infections that may result in death.

Although there is no vaccine for HIV, there are Pre-exposure prophylaxis (or PrEP) medicines that can be taken by people at high risk of contracting the infection. PrEP reduces the risk of getting HIV from sex by about 99 per cent.