Naturally men don’t face these risks if they choose to have unprotected sex, so the safety standards for any contraceptives they might take have a higher bar to get across.

Take hormonal male contraceptive pills. Numerous versions have been developed stretching back to the 1970s, when researchers injected volunteers with testosterone each week for several months and then checked if it had affected sperm production. One early trial found that it was extraordinarily effective – with just five pregnancies after the equivalent of one person using the method for 180 years. Later studies looked at whether this could be increased even further by adding in a second hormone, such as progestin – a synthetic version of the female reproductive hormone progesterone.

However, there was a problem: hormone therapies come with a well-established smorgasbord of side-effects – many of which will be familiar to women taking the contraceptive pill. Testosterone alone can lead to acne, oily skin and weight gain, among others, and this led to some trials being halted early.

“There have been very successful trials of male hormonal contraceptive injections,” says Walker, who gives the example of the contraceptive injection, which was found to be almost 100% effective in suppressing sperm concentrations. “That worked extremely well,” says Walker. “But it was halted because of worries around side effects, like mood changes and skin changes – which those of us who work with female contraception weren’t really surprised about.”

A path to acceptance

However, a number of non-hormonal contraceptive options for men have also been proposed, including a vaccine that targets a protein involved in sperm maturation and a kind of temporary vasectomy, reversible inhibition of sperm under guidance (RISUG).

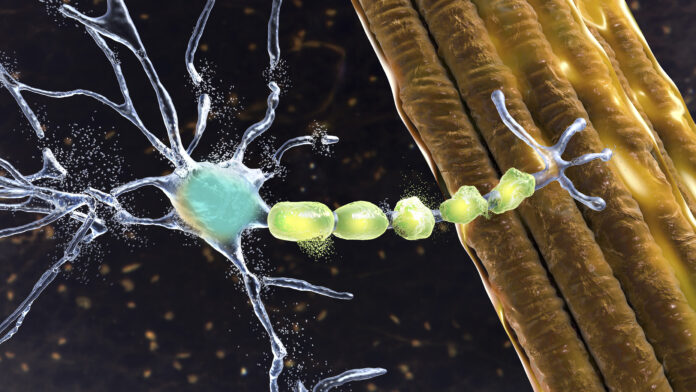

RISUG involves injecting a synthetic polymer into the tube that carries sperm out of the testes – the vas deferens – to block the exit of sperm. It was originally developed as a way to sterilise water pipes, but later adapted to be safe inside the human body. It’s currently undergoing Phase III clinical trials – the final stage of testing before a treatment is approved – in India.

However, as with the clean-sheets contraceptive pill, even non-hormonal contraception may be unappealing to some men.

“I think it is true that, in my experience of talking to men about this, men are worried about future fertility and about unknown side effects that may only become known years after using a product,” says Walker. “They’re worried about the effect on their performance, how they feel about sex.”

Funding can also be an issue. In the case of the clean sheets pill, a survey by the Parsemus Foundation – a non-profit based in the US that supports neglected areas of medical research – found that, while 20% of men said they wouldn’t take it, an equal proportion said that they would. The rest said they were undecided. And yet, the therapy lost its funding before the necessary animal and human trials could take place.

Walker points out that there are several charities working hard to fund research into male contraceptives, but speculates that pharmaceutical companies may have less incentive to develop them when female contraceptive methods work so well. She suggests they’re just not going to get the same return on their investment that they would in a pill-free world.

“I think people are more risk-averse in the world of male contraception,” says Walker. “Men are more risk-averse, ethics panels are more risk-averse, and possibly pharmacy companies are more risk averse.” Walker has been working in the field of contraception and reproductive health for at least 15 years, and while she used to believe that we’d have a male pill soon, this hope has faded. “I’m no longer optimistic [about this],” she says. “Each method seems to hit the hurdle of acceptability.”

Who knows, perhaps the latest promising candidate – the protein that temporarily immobilises sperm in mice – will finally overcome decades of challenges. But it is unlikely many women around the world will be holding their breath.

—

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List” – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.