Researchers at Arizona State University (ASU) and Banner Alzheimer’s Institute have uncovered an unexpected connection between cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a common virus that can persist in the gut, and the development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in a subset of people. The findings are published in the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

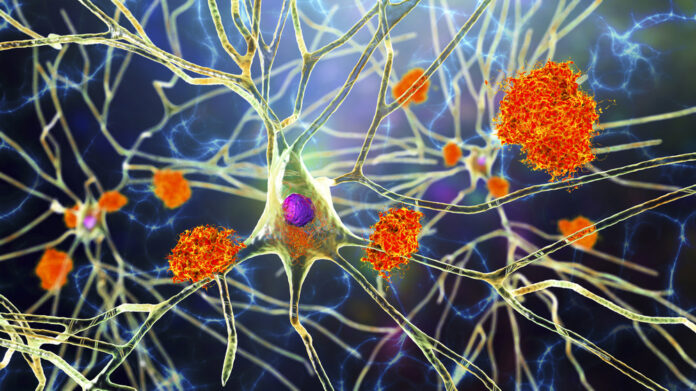

“We think we found a biologically unique subtype of Alzheimer’s that may affect 25% to 45% of people with this disease,” said Ben Redhead, MD, co-first author of the study and professor of dementia research at ASU-Banner Neurodegenerative Disease Research Center. “This subtype of Alzheimer’s includes the hallmark amyloid plaques and tau tangles—microscopic brain abnormalities used for diagnosis—and features a distinct biological profile of virus, antibodies, and immune cells in the brain.”

Most people are exposed to HCMV in the first few decades of life. While HCMV typically remains dormant, in some people, the virus may linger in an active state in the gut and travel to the brain via the vagus nerve. Once this has occurred, HCMV may trigger microglia, the brain’s immune cells, to express a gene called CD83, which plays a role in the brain’s immune response. The activation of CD83(+) microglia is thought to contribute to inflammation and neuronal damage, hallmarks of AD.

The researchers’ findings align with a study published earlier this year in Nature Communications that the postmortem brains of patients with AD were more likely to harbor CD83(+) microglia than those without the disease. Further investigation of why this was true uncovered an antibody present in the intestines of those with AD indicating that an infection of some sort could be playing a role in this form of the disease. The new study positively linked the CD83(+) microglia to the presence of HCMV antibodies in the intestines and cerebrospinal fluid of the same patients. The researchers also confirmed the presence of HCMV in the vagus nerve, which suggests the virus may reach the brain by traveling through this neural pathway.

The vast majority of individuals are exposed to HCMV at some point in their lives with 80% of people showing evidence of antibodies by age 80. However, the investigator detected intestinal HCMV in only a portion of people and the presence of these antibodies appears to be relevant in the presence of the virus in the brain.

While the team’s two studies have shown the impact viruses may have on brain health and neurodegeneration, continued research is needed to understand how this affects brain health and tau pathology. To support further research in this area, the ASU-Banner team is developing a blood test to identify patients with this type of chronic intestinal HCMV infection. This should allow for more detailed study of this subset of AD, as well as support its use in conjunction with other blood tests to study if using existing antiviral medications could help treat, or prevent, this form of the disease.