This transcript has been edited for clarity.

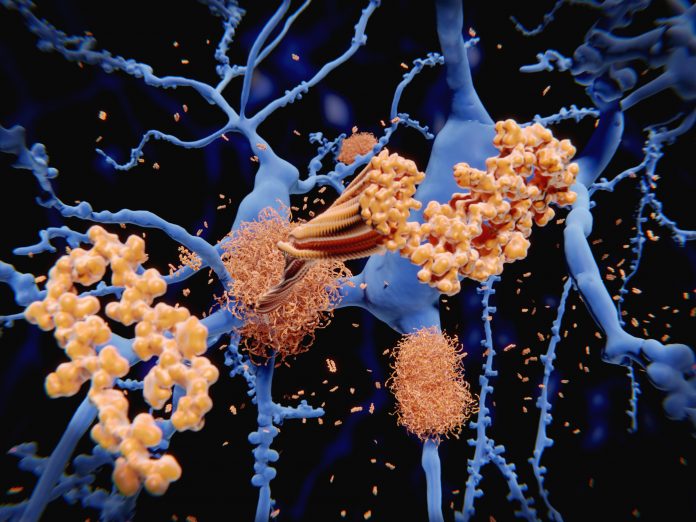

Hello. my name is Dr Lisa Barnes. I am a cognitive neuropsychologist and professor within the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, Illinois. I’m here to talk about lifestyle interventions that may prevent or delay cognitive impairment. Cognitive impairment, or loss of memory and thinking skills, is a hallmark feature of Alzheimer’s disease dementia.

Alzheimer’s has become a global public health priority. The number of people suffering from dementia is substantial, with an estimated 55 million globally. For a public health problem of this magnitude, prevention is a critical component to reducing the burden of Alzheimer’s, both for people with the condition and for those who care for them.

A growing body of research has demonstrated that there are multiple overlapping causes of dementia. The strongest evidence-supporting strategies to prevent dementia come from large observational studies. Though there can be a large amount of conflicting information on brain health, there have been two major reports that nicely summarize the current evidence on prevention strategies.

In 2017, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine committee was commissioned by the National Institute on Aging to review interventions for preventing cognitive decline and dementia based on findings from a number of large randomized clinical trials. Findings from that review concluded that the available evidence was inconclusive and that none of the interventions showed strong enough evidence to message the public about dementia prevention.

However, the report did find promising evidence of the potential benefit of three types of interventions: cognitive training, blood pressure management in people with hypertension, and increased physical activity. The second major report was from the Lancet Commission in 2020. They reviewed existing evidence from both clinical trials and observational studies and identified 12 modifiable risk factors that account for an estimated 40% of dementia risk worldwide. These risk factors included low education, hearing loss, obesity, hypertension, late-life depression, smoking, physical inactivity, diabetes, infrequent social contact, traumatic brain injury, alcohol consumption, and air pollution.

Managing Cardiovascular Risk Factors

What is the best advice to reduce your risk for cognitive impairment in late-life and maintain a healthy brain? If you’re focused on prevention, one consistently reported risk factor is cardiovascular disease, especially in midlife. For example, hypertension and high cholesterol during midlife have both been associated with risk for cognitive impairment or dementia in various studies. These observational studies typically provide targets that can be investigated in randomized clinical trials.

If you take hypertension, for example, a recent trial was conducted to evaluate the effect of intensive blood pressure control on risk for dementia. This randomized controlled clinical trial, called SPRINT, enrolled over 9000 adults aged 50 years or older. Participants had to have hypertension but no diabetes or history of stroke. They recruited across over 100 sites in the United States.

Participants were randomly assigned to have either a standard-treatment group, therefore aiming for a systolic blood pressure goal

The SPRINT MIND study, which was designed as a part of SPRINT, looked at the occurrence of dementia as the primary outcome. The cognitive assessment and determination of dementia continued after the SPRINT trial ended. Results from that analysis showed that participants assigned to the intensive-treatment group had a reduction in all-cause dementia, but it was not statistically significant. They did have statistically significant reductions in the risk of developing mild cognitive impairment, however.

Multidomain Interventions Show Promise

Based on results from numerous observational studies, we’ve learned that targeting several risk factors simultaneously will probably lead to better preventive effects, what we now call multidomain interventions. Another example of a successful multidomain trial is the FINGER trial, which was a 2-year trial that enrolled over 1200 adults aged 60-77 years in Finland. Participants had to be at high risk for cardiovascular disease and have cognition at a level slightly lower than that expected for age.

About half were randomly assigned to an intensive multidomain intervention consisting of exercise, dietary counseling, cognitive training, and cardiovascular risk factor control. The other half was assigned to a control condition, which received general health advice. At baseline, all participants were given oral and written information and advice on healthy diet and physical, cognitive, and social activities that are beneficial for managing vascular risk factors.

The intervention group additionally received four intervention components in individual and group sessions. They received tailoring of their diet by study nutritionists with weekly goals. They received a weekly exercise program, including strength and aerobic training. They received cognitive training in group and individual sessions. Social activities were stimulated through the different group meetings of all the intervention components. Finally, they had management of metabolic and vascular risk factors based on national evidence-based guidelines.

The primary outcome was performance on a battery of neuropsychological tests administered at baseline and at 12 and 24 months after they were randomized. They found a significant beneficial effect of the intervention, such that the change in the total score on the cognitive battery at 2 years was 25% higher in the intervention group than in the control group. This was a really promising result, showing that a combination of lifestyle factors can protect cognition in older adults with an increased risk for cognitive decline.

But this was an older population in Finland, and generalizability to other cultural contexts is not entirely clear. A series of new trials are currently being conducted within a collaborative international network called World-Wide FINGERS and includes several European countries, the United States, China, Singapore, and Australia.

The trial in the US is called U.S. POINTER. It’s a large, multisite, randomized controlled trial that is similar to FINGER, the Finland trial, but it has been adapted to American culture and delivered within the community with a diverse and representative population of older Americans. The goal of U.S. POINTER is to investigate the effects of random assignment to one of two lifestyle interventions for 2 years. They’re going to look at cognitive function in about 2000 older adults who are at risk for cognitive decline and dementia owing to well-established risk factors. Both interventions were designed to target specific lifestyle behaviors that have been linked to brain health, but they are going to differ in format and intensity. The results from that trial are pending and should be available approximately in the next 2 years.

In summary, this is a really exciting time for the Alzheimer’s field. A growing body of research is suggesting that interventions targeting multiple risk factors simultaneously might be beneficial in preventing cognitive decline and dementia in late life. It’s critical that we design and implement effective interventions to reduce the risk. This can be achieved through primary prevention, focusing on lowering the dementia risk for cognitively normal individuals. We can start even as early as midlife. Thank you.