Colorado has seen more severe strep cases than usual since November, and two children’s deaths have been linked to the infections.

The children’s death certificates haven’t been finalized, so it’s not confirmed whether their Group A streptococcus infections were the cause of death, state epidemiologist Dr. Rachel Herlihy said. Both were not yet old enough for school.

Most Group A streptococcus infections are mild, causing what’s popularly called strep throat. Less frequently, the bacteria can cause scarlet fever, which involves a rash and can lead to organ damage if untreated.

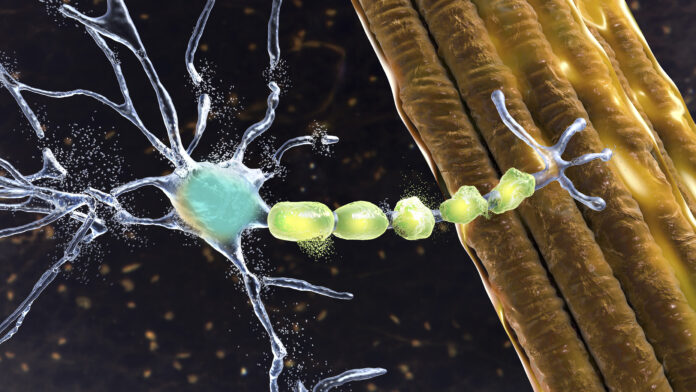

The state only tracks strep A infections, which are more severe than strep throat or scarlet fever, Herlihy said. In “invasive” infections, the bacteria move into the lungs, the bloodstream, the nervous system or the tissues surrounding a wound.

Typically, the state averages one or two invasive strep A infections in a month, but there have been 11 reported in the Denver area since the start of November, she said. (The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment doesn’t track strep A infections statewide.)

The last time a Colorado child died of invasive strep A was in 2018.

Invasive strep A infections often follow a viral infection that damages the lining of the throat enough to let the bacteria through, Herlihy said. Colorado and the rest of the country saw unprecedented hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, which usually causes a cold, but can be severe in young children. Influenza season also started early, and parents have anecdotally reported that their kids seem to be picking up more respiratory bugs than usual.

“We’ve seen a very large number of viral infections,” Herlihy said. “One of the strategies (to prevent invasive strep) is to prevent that initial infection.”

The state health department is also investigating an increase in severe infections with Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus, which also tend to cause secondary infections. There’s no vaccine for strep A or Staphylococcus aureus, but children and older adults typically are vaccinated against multiple strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Parents can prevent secondary infections, including strep A, by making sure their children are up to date on their shots for flu, COVID-19 and chickenpox, Herlihy said. Handwashing also can reduce the odds of catching strep A, because the bacteria spread via respiratory droplets when someone coughs or sneezes, as well as through shared items like cups.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is investigating whether there’s a larger pattern of increasing invasive strep A infections. In a typical year, the CDC estimates about 5.2 million people get throat infections from strep A, and between 14,000 and 25,000 develop invasive disease.

The United Kingdom has seen an unusually early season for scarlet fever and other strep A infections, which typically peak there between February and April, though it’s not clear if the total number of severe cases will be higher than in a normal year.

Signs of possible invasive strep A infections include:

- Red, swollen skin around a wound, which may be painful when touched

- Skin ulcers, blisters or oozing

- Fever and chills

- Muscle or joint pain

- Nausea, vomiting or diarrhea

- Dizziness

- Rapid breathing

- Fast heart rate

- Fatigue

- Uncontrollable movements

The symptoms of invasive strep A would be concerning even if caused by a different infection, so parents who see their child isn’t getting better don’t need to try to diagnose them before seeking care, said Dr. Christine Jelinek-Berents, a pediatrician at Kaiser Permanente Colorado.

“Families don’t necessarily need to know all the symptoms of strep,” she said.

Subscribe to bi-weekly newsletter to get health news sent straight to your inbox.