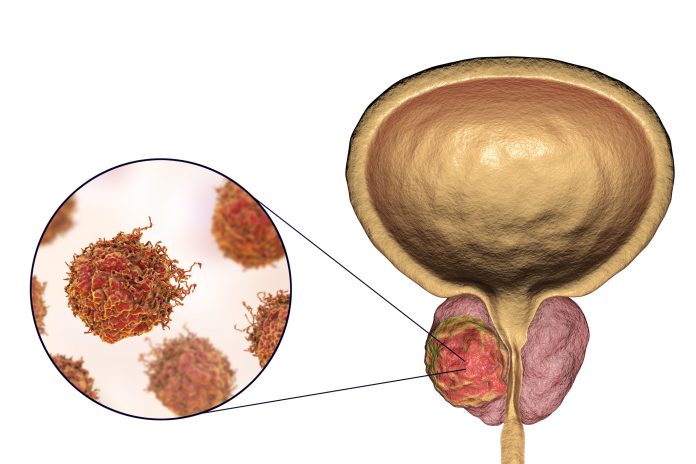

Research led by the University of California, Los Angeles, shows that conventional imaging may not be able to correctly assess prostate cancer patients whose cancer has metastasized and spread to other areas of the body.

The team looked at a group of people with prostate cancer who were previously classed as non-metastatic using conventional cancer imaging. When they used prostate-specific membrane antigen–positron emission tomographic/computed tomographic (PSMA-PET/CT) imaging instead of conventional imaging almost half of the people screened showed evidence of metastases.

“Our study demonstrates the critical role of PSMA-PET in accurately staging prostate cancer, which can significantly impact treatment decisions and outcomes,” said senior author of the study Jeremie Calais, associate professor at the department of molecular and medical pharmacology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, in a press statement.

PSMA-PET is a relatively new imaging technology that uses small amounts of radio tracers to bind to prostate cancer cells in the patient’s body. This imaging agent then allows these cells to be seen using PET imaging. Since the first PSMA radiotracer was approved more than three years ago it has become a relatively widespread prostate cancer imaging technique in the U.S.

This study, published in JAMA Network Open, tested 182 prostate cancer patients who would have been eligible to take part in a completed Phase III study called the EMBARK study. This trial tested the efficacy of enzalutamide with or without leuprolide for treatment of high-risk prostate cancer. Eligibility for the study relied on conventional imaging ruling out prostate cancer metastases.

Using PSMA-PET/CT, the researchers found that 46% of patients had at least one metastasis and 24% had five or more metastases. “We anticipated that PSMA-PET would detect more suspicious findings compared to conventional imaging. However, it was informative to uncover such a high number of metastatic findings in a well-defined cohort of patients resembling the EMBARK trial population that was supposed to only include those without metastases,” said Adrien Holzgreve, a visiting assistant professor at the David Geffen School of Medicine and first author of the study.

PSMA-PET/CT imaging is still relatively new, but these results support others showing its superiority over more conventional imaging for giving accurate diagnostic and prognostic information for patients.

“We have good rationales to assume that it is helpful to primarily rely on PSMA-PET findings,” said Holzgreve. “But more high-quality prospective data would be needed to claim superiority of PSMA-PET for treatment-guidance in terms of patient outcome. However, we are confident PSMA-PET will continue to advance prostate cancer staging and guide personalized therapies.”

![Best Weight Loss Supplements [2022-23] New Reports!](https://technologytangle.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/p1-1170962-1670840878.png)