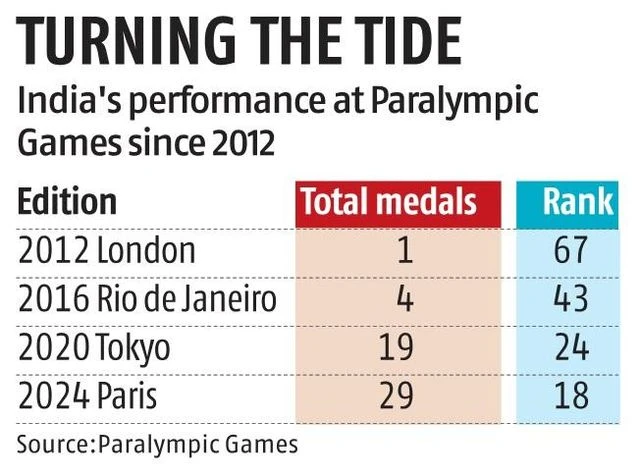

India’s Paralympians will look back at their campaign in Paris with pride, as they glittered on the big stage with a record-smashing 29 medals.

In doing so, they bettered their performance at the Tokyo Games three years ago, when they bagged an impressive haul of 19 medals.

While the upswing in the performance of these para-athletes has brought them much-needed recognition, the brand ecosystem and corporate bigwigs are yet to loosen their purse strings.

“The perspective has changed. From facilities to funding, things are now getting better,” says Rubina Francis, who grabbed bronze in pistol shooting.

)

Shooter and Paralympic medallist Mona Agarwal, a beneficiary of the para Khelo India scheme, the flagship government programme aimed at unearthing Olympic superstars, talks about the impetus needed at the grassroots level.

“I am a medallist now. I know that I will have enough support. But what about the ones who are starting their journey? Brands or government, they should come early,” Agarwal says, adding that if she received this push early in life, it would have been more helpful.

“Nevertheless, I had no support, and any scheme, Khelo India in my case, can help a lot,” Agarwal adds. “A monthly support of Rs 10,000 was, at least, enough to pay the salary of my escort,” she adds.

Although para-athletes highlight the government’s push and the rise of non-government organisations like Olympic Gold Quest and GoSports, they agree that the brand ecosystem is yet to unlock a plethora of opportunities.

“In terms of brand deals and endorsements, there is still a huge gap between able-bodied athletes and para-athletes. Going forward, more visibility is required,” Paralympian shooter Avani Lekhara from Rajasthan, who became the first Indian woman to bag two medals at the Paralympics, tells Business Standard.

While brands are now coming forward to partner with the Paralympic Committee of India, individual player brand deals are significantly low.

“Talks are on but they are mostly short-term engagement and not endorsement deals,” says Neerav Tomar, founder and managing director, IOS Sports, the agency that manages multiple athletes, including Paralympians Sumit Antil and Nishad Kumar.

“The number (of deals for Olympians and Paralympians) is not really comparable at this point,” Tomar adds.

“Historically, there hasn’t been much representation around para-athletes from a brand perspective. With their best medal tally in Paris, it has triggered considerable organic interest,” says Vishal Jaison, co-founder, Baseline Ventures.

“Multiple queries and discussions are taking place,” he notes.

Is the government funding enough to sponsor athletes at the global level? Experts and players reckon that in para-sports, more funds are needed owing to the intricacies and the specialised equipment.

“Corporations can provide additional funding for training, equipment, and travel,” says former Paralympic fencer Vibhas Sen.

He highlights that businesses can offer long-term security by arranging the post-sport career paths and mentorships.

Para shooter and silver medal winner at Paris Games, Manish Narwal, says it may take 4-5 years more for the corporate world to take up interest in para-sports.

“It is because of foundations like OGQ, GoSports and government recognition that athletes have to worry less about funding,” Narwal explains.

Balwan Singh, a gold medallist at the 2006 (Fespic) Asian Games in track-and-field, says that on his return, he received Rs 1,00,000 as prize money from the Delhi government, while able-bodied athletes received Rs 10,00,000.

“It was years of legal battle. The prize money is at par now,” Singh adds.

“The training was a challenge then, jisko jahan jagah milti thi, vahin train karte the (Athletes used to train wherever they got space),” he says.

“There’s much more media coverage, public interest, and awareness now. The infrastructure for para-athletes has improved considerably,” Sen adds.

“In 2017, when I took up archery, nobody knew the sport,” says para-archer, and Paris medallist Rakesh Sharma.

While the Khelo India scheme was launched in 2017, the programme for para athletes began only in 2023.

Tokyo Olympics: The turning point

Abiba Ali, 20, a para-athlete who trains at New Delhi’s Siri Fort Sports Complex, says she sees Lekhara as her inspiration.

“An accident in 2015 that left me wheelchair-bound and clueless about the future,” Ali says.

“I am now targeting the next Olympics,” she adds.

“While I was looking for options, Avani’s story piqued my attention. When she won gold at Tokyo, it was my final clarion call to take up the sport,” Ali adds.

Francis and Narwal agree that the Tokyo Olympics has changed the way para-athletes are perceived.

“With consistent performances of para athletes at the global stage, and the increased international visibility, especially the last two editions of the Olympics, brands are open to exploring long-term, and meaningful partnerships,” Jaison adds.

For now, it is time for the country’s Paralympians to bask in the new-found glory.