The ozone ‘hole’, once considered to be the gravest danger to planetary life, is now expected to be completely repaired by 2066, a scientific assessment has suggested. In fact, it is only the ozone layer over Antarctica — where the hole is the most prominent — which will take a long time to heal completely. Over the rest of the world, the ozone layer is expected to be back to where it was in 1980 by 2040 itself, a UN-backed scientific panel has reported.

The recovery of the ozone layer has been made possible by the successful elimination of some harmful industrial chemicals, together referred to as Ozone Depleting Substances or ODSs, through the implementation of the 1989 Montreal Protocol. The assessment has reported that nearly 99 per cent of the substances banned by the Montreal Protocol have now been eliminated from use, resulting in a slow but definite recovery of the ozone layer.

Damage to the ozone layer

The depletion of the ozone layer, first noticed in the early 1980s, used to be the biggest environmental threat before climate change came along. Ozone (chemically, a molecule having three Oxygen atoms, or O3) is found mainly in the upper atmosphere, an area called stratosphere, between 10 and 50 km from the Earth’s surface. It is critical for planetary life, since it absorbs ultraviolet rays coming from the Sun. UV rays are known to cause skin cancer and many other diseases and deformities in plants and animals.

Though the problem is commonly referred to as the emergence of a ‘hole’ in the ozone layer, it is actually just a reduction in concentration of the ozone molecules. Even in the normal state, ozone is present in extremely low concentrations in the stratosphere. Where the ‘layer’ is supposed to be the thickest, there are no more than a few molecules of ozone for every million air molecules.

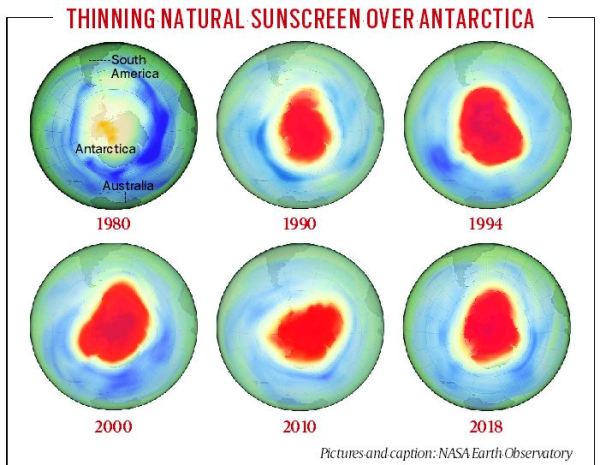

In the 1980s, scientists began to notice a sharp drop in the concentration of ozone. This drop was much more pronounced over the South Pole, which was later linked to the unique meteorological conditions — temperature, pressure, wind speed and direction — that prevail over Antarctica. The ozone hole over Antarctica is the biggest during the months of September, October, and November.

By the middle of 1980s, scientists had figured out that the chief cause of ozone depletion was the use of a class of industrial chemicals that contained chlorine, bromine or fluorine. The most common of these were the chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, that were used extensively in the airconditioning, refrigeration, paints, and furniture industries.

Improvement in the situation

The ozone hole has been steadily improving since 2000, thanks to the effective implementation of the Montreal Protocol.

The latest scientific assessment has said that if current policies continued to be implemented, the ozone layer was expected to recover to 1980 values by 2066 over Antarctica, by 2045 over the Arctic, and by 2040 for the rest of the world.

The elimination of ozone-depleting substances has an important climate change co-benefit as well. These substances also happen to be powerful greenhouse gases, several of them hundreds or even thousands of times more dangerous than carbon dioxide, the most abundant greenhouse gas and the main driver of global warming. The report said that global compliance to the Montreal Protocol would ensure the avoidance of 0.5 to 1 degree Celsius of warming by 2050. This means that if the use of CFCs and other similar chemicals had continued to grow the way it did before they were banned, the world would have been 0.5 to 1 degree Celsius warmer than it already is.

In fact, it was with this climate change objective in mind that the Montreal Protocol was amended in 2016 to extend its mandate over hydrofluorocarbons, or HFCs, that have replaced the CFCs in industrial use. HFCs do not cause much damage to the ozone layer — the reason they were not originally banned — but are very powerful greenhouse gases. The Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol seeks to eliminate 80-90 per cent of the HFCs currently in use by the year 2050. This is expected to prevent another 0.3 to 0.5 degree Celsius of global warming by the turn of the century.

Precedent for climate action

The success of the Montreal Protocol in repairing the ozone hole is often offered as a model for climate action. It is argued that emissions of greenhouse gases can also similarly be curtailed to arrest rapidly rising global temperatures.

However, the parallels of elimination of ODSs with greenhouse gases are limited. The use of ODSs, though extensive, was restricted to some specific industries. Their replacements were readily available, even if at a slightly higher cost initially. The impact of banning these ozone-depleting chemicals was therefore limited to these specific sectors. With some incentives, these sectors have recovered from the initial disruption and are thriving again.

The case of fossil fuels is very different. Emission of carbon dioxide is inextricably linked to the harnessing of energy. Almost every economic activity leads to carbon dioxide emissions. Even the so-called renewable energies, like solar or wind, have considerable carbon footprints right now, because their manufacturing, transport, and operation involves the use of fossil fuels.

The emissions of methane, the other major greenhouse gas, comes mainly from agricultural practices and livestock. The impact of restraining greenhouse gas emissions is not limited to a few industries or economic sectors, but affects the entire economy, and also has implications for the quality of life, human lifestyles and habits and behaviours. Climate change, no doubt, is a far more difficult and complex problem than dealing with ozone depletion.

![Best Weight Loss Supplements [2022-23] New Reports!](https://technologytangle.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/p1-1170962-1670840878.png)