Some of the earliest observations of human health have proposed a connection between what is happening in the human gut and mental health—the now well-known gut–brain axis. However, researchers only began to make significant headway in these studies roughly 30 years ago. Today, research on the influence of the gut microbiome is flourishing and extends well beyond mental health as direct connections are made between microbiome composition and diseases like cancer, irritable bowel disease (IBD), obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disorders.

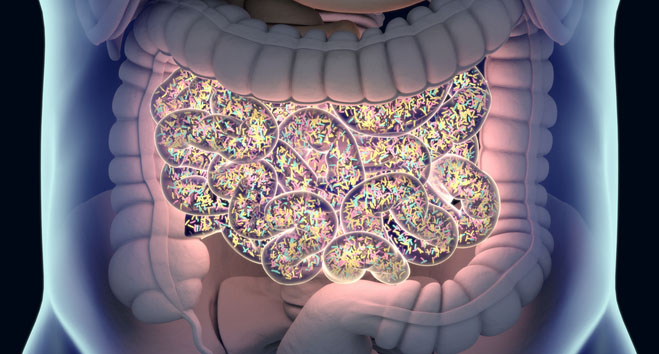

It only makes sense that the gut microbiome would have a significant effect on disease development. After all, it has been estimated that gut microbiota comprise 100 trillion, or more, individual microorganisms—or at least three times the total number of cells in the human body.

Diet plays a significant role in shaping the composition, function, and diversity of the gut microbiome. Research led by Catherine Stanton, PhD, of APC Microbiome Ireland, University College Cork, and the Teagasc Food Research Centre at Moorepark published in July by Nature Reviews Microbiology delved into the effects of different diets on gut microbiota and the resulting effects on human health.

“Understanding the profound impact of varied diets on the microbiome is crucial, as it will enable us not only to make well-informed dietary decisions for better metabolic and intestinal health, but also to prevent and slow the onset of specific diet-related diseases that stem from suboptimal diets,” wrote Stanton and colleagues.

Understanding the human gut microbiome is no small undertaking given the complex interactions of the trillions of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and protozoa in its composition. Further, this intricate system is influenced by external factors from the time we are born, with the result being that no two human gut microbiomes are the same. They are as individualized as our fingerprints.

That said, researchers can draw conclusions on how diet broadly affects the composition of our gut flora, whether it supports different types of beneficial microbes or effectively lowers their populations to unhealthy levels.

From Stanton and collaborators: “In adulthood, although the microbiome tends to be relatively stable, external factors, particularly diet, substantially influence its composition and function. This complex interplay among nutrients, the microbiota, and the immune system serves as a critical regulatory mechanism for preserving homoeostasis and defending against external pathogens. Studies have shown that both short-term and long-term dietary regimes alter the composition and functionality of the gut microbiota, demonstrating the power of diet in influencing human health.”

The implications here are clear. While it is still early, the acceleration of gut microbiome research has been aided significantly in recent years by advances in sequencing and machine learning algorithms that can effectively sort through the mountains of data being generated. These advances may soon point the way to clinical dietary interventions that not only help mitigate disease risk, but also treat disease at its earliest stages.

Senior Principal Research Officer

Teagasc Food Research Centre

Studies are already underway to find whether microbes contained in fermented foods can tackle health conditions. According to Paul Cotter, PhD, senior principal research officer at the Teagasc Food Research Centre, who led a study on the microbiome of food products: “We are carrying out a study whereby we have individuals in a number of different countries who are consuming a particular milk kefir product over a six-month period to see how that impacts on their health and their microbiome. It contains a group of microbes that are designed to reduce cholesterol. We have evidence of that from an earlier small human study where we saw benefits.”

Maintaining or degrading the gut microbiota

Not surprisingly, diets considered healthy, such as the Mediterranean diet, help support a healthy gut as they are rich in fiber, fruits, and vegetables. Fermented foods such as kombucha, kefir, kimchi, and sauerkraut carry their own populations of microbes and are also highly beneficial.

Lab Director

Xishuangbanna Tropical

Botanical Garden

One dietary component that can significantly influence the building or maintenance of a healthy gut microbiome is fiber. The key process here is fermentation of the fibers by gut microbes. In particular, indigestible polysaccharides with complex structures promote the growth of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which produce bacteria that are considered the “foundation species” for maintenance of a healthy gut ecosystem, said Ping Zhang, PhD, laboratory director at Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy, in the Yunnan province of China.

“Generally speaking, foods containing different sources of dietary fiber with different structures are likely to promote diversity of the gut microbiota,” said Zhang. “Some foods may be considered ‘superior’ for providing the desired diversity of a healthy microbiota, for example, whole-grain cereals—corn, wheat, sorghum, and oats—legumes, sweet potatoes, and bananas.”

People whose diets consistently include these foods, as well as a balance of fruits and proteins, tend to show a broad variety of species in their microbiome. “Alpha diversity of gut microbiota, an ecological concept that refers to the number and distribution of different species, appears to be a reliable marker of microbiome health,” noted a team of Italian researchers led by Gianluca Ianiro, PhD, a professor of gastroenterology at the Catholic University, Rome.

Conversely, the so-called Western diet and others that are high in fats, sugars, and processed foods undermines this microbial diversity, often resulting in inflammation and dysregulation of the immune system. People with obesity exhibit less diversity in the microbiome, including producers of the amino acid butyrate. Butyrate inhibits pro-inflammatory immune cells like M1 macrophages and neutrophils by reducing the production of proinflammatory cytokines while also activating anti-inflammatory cells like Tregs and M2 macrophages.

“Altered composition in the gut microbiome, manifested by reduction of beneficial keystone bacterial species and enrichment of detrimental microbes, has been observed in many diseases, such as infectious disease, cancer, metabolic disease, cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disease, and allergic and atopic diseases,” said Zhang.

The microbiome and neurodegenerative disease

While the microbiome’s influence in the development of diseases such as IBD, type 2 diabetes, and autoimmune disorders has received plenty of attention, a growing body of evidence is showing that it also influences neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s disease (PD).

The association between PD and gastrointestinal disorders like IBD has been known for some time and helped give rise to the term “institutional colon” due to its high prevalence in mental health facilities. Now, however, researchers have flipped the script. Instead of proposing that PD causes the gastrointestinal symptoms, they have shown that gastrointestinal issues are prodromal symptoms of PD and that its genesis lies in the gut.

Last month, researchers from Tufts, Harvard, and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston published research in JAMA Network Open showing that upper gastrointestinal mucosal damage was associated with increased risk of developing PD. Further, symptoms of gastrointestinal disease presented as early as 20 years before the development of the hallmark motor symptoms of PD.

With evidence growing for the “gut-first” hypothesis of how PD begins, other researchers have looked to microbiome dysbiosis as a potential driver of PD while examining how dietary interventions may mitigate this risk or even arrest disease development.

Department of Epidemiology

UCLA

PhD candidate Dayoon Kwon and colleagues at UCLA published data in April in npj Parkinson’s Disease suggesting that the gut microbial profiles of PD patients are influenced by dietary habits. “We observed differences in the microbiome in relation to diet quality, as well as the intake of dietary fiber and added sugar. These findings align with previous studies and further suggest that a healthy diet may have beneficial effects on the gut microbiome in PD patients,” she said.

In particular, the team looked at the impact of added sugars on the gut microbiome in PD patients. Their previous study from 2023, published in Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, detailed the effects of all sugars (both naturally occurring and added) in the diets of PD patients and healthy controls.

“We observed that PD patients tend to consume higher amounts of both total and added sugars,” Kwon said. “Specifically, we found dietary differences between PD patients and controls, where PD patients consumed a diet lower in overall quality, characterized by higher intakes of carbohydrates, total sugars (including naturally occurring sugars like fructose, glucose, and lactose), and added sugars.”

A review article published in Current Nutrition Reports earlier this year by dieticians Şerife Ayten, PhD, and Saniye Bilici, PhD, of Gazi University in Ankara, Türkiye noted that “some dietary patterns can affect neurodegenerative diseases’ progression through gut microbiota composition, gut permeability, and the synthesis and secretion of microbial-derived neurotrophic factors and neurotransmitters.”

While acknowledging the lack of research on the abilities of specific diets (ketogenic, Mediterranean, vegetarian, and Western diet) to affect the progression of neuroinflammation in both Alzheimer’s disease and PD, research has shown that the ketogenic diet “displays promising potential in ameliorating the clinical trajectory of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease,” wrote Ayten and Bilici. “Vegetarian and Mediterranean diets, known for their anti-inflammatory properties, can be effective against Parkinson’s disease, which is related to inflammation in the gut environment.”

Not surprisingly, the Western diet was associated with reduced gut microbial diversity and microbes, a condition that ultimately leads to neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment.

But with the focus now turning to the prodromal phases of PD, there is rising optimism that treatment could eventually comprise dietary interventions to head off the disease. But early intervention is key. Kwon noted that the UCLA team conducted a stratified analysis in their most recent research, which showed the microbiome’s response to dietary fiber intake varies based on the duration of PD.

“Specifically, among patients with shorter disease durations ( 10 years),” said Kwon. “This suggests that in the early stages of PD, the microbiome is more responsive to dietary fiber, potentially enhancing its beneficial impact.”

A possible reason for this strategy being less effective against longer duration PD, Kwon noted, was that the microbial imbalance in these patients was more entrenched due to the cumulative effects of the disease on the gut environment.

“Our study on the gut microbiome and diet in PD underscores the need for longitudinal research to understand the causal relationships and temporal dynamics between diet, the microbiome, and PD progression,” Kwon concluded. “If these dietary effects are validated in further research, clinicians could potentially recommend specific dietary modifications as part of early intervention strategies to manage or even slow the progression of PD.”

Looking to the future

Scientists understand that current research only reveals the tip of the iceberg when it comes to modulating the microbiome to treat disease via dietary intervention. Nonetheless, there is ample evidence to point to a future where this is possible.

At her lab in the Yunnan province of China—known as the “plant kingdom” and a hot spot for ecological study—Zhang sees potential in biodiversity. She notes that the plant resources there remain largely unexplored and points to a few emerging studies to bolster her case on their healing powers. In one instance, the lab has identified a therapeutic spice that has potential for treating colitis and diabetes.

“The nutritional value of the plant foods indigenous to this region in promoting health is great, such as the remarkable effects of the bamboo shoot fiber as a novel dietary fiber in controlling body weight and modifying the gut microbiome as we demonstrated in a paper several years ago,” Zhang noted.

Cotter believes that his team’s development of a comprehensive food microbiome database can be leveraged to create foods containing specific beneficial microbes to treat a range of conditions. For instance, understanding communities of microbes and their metabolites could inform the design of foods that help those with gluten intolerance break down the gluten in their system or identify different microbes that help digest other undesirable food components.

“This could be triggering things in the gut–brain axis and you could bring these communities together in a tailor-made fashion—in almost a personalized nutrition scenario,” Cotter said. “So, a fermented food might be good for their IBD symptoms or to address their anxiety, or to lower their cholesterol. These are all potentially possible in the future.”

Chris Anderson, a Maine native, has been a B2B editor for more than 25 years. He was the founding editor of Security Systems News and Drug Discovery News, and led the print launch and expanded coverage as editor in chief of Clinical OMICs, now named Inside Precision Medicine.