‘In all my novels, I’ve always tried to get very close to human truths, the things that define what it is to be a human being…,’ says Paul Lynch.

| Photo Credit: Getty Images

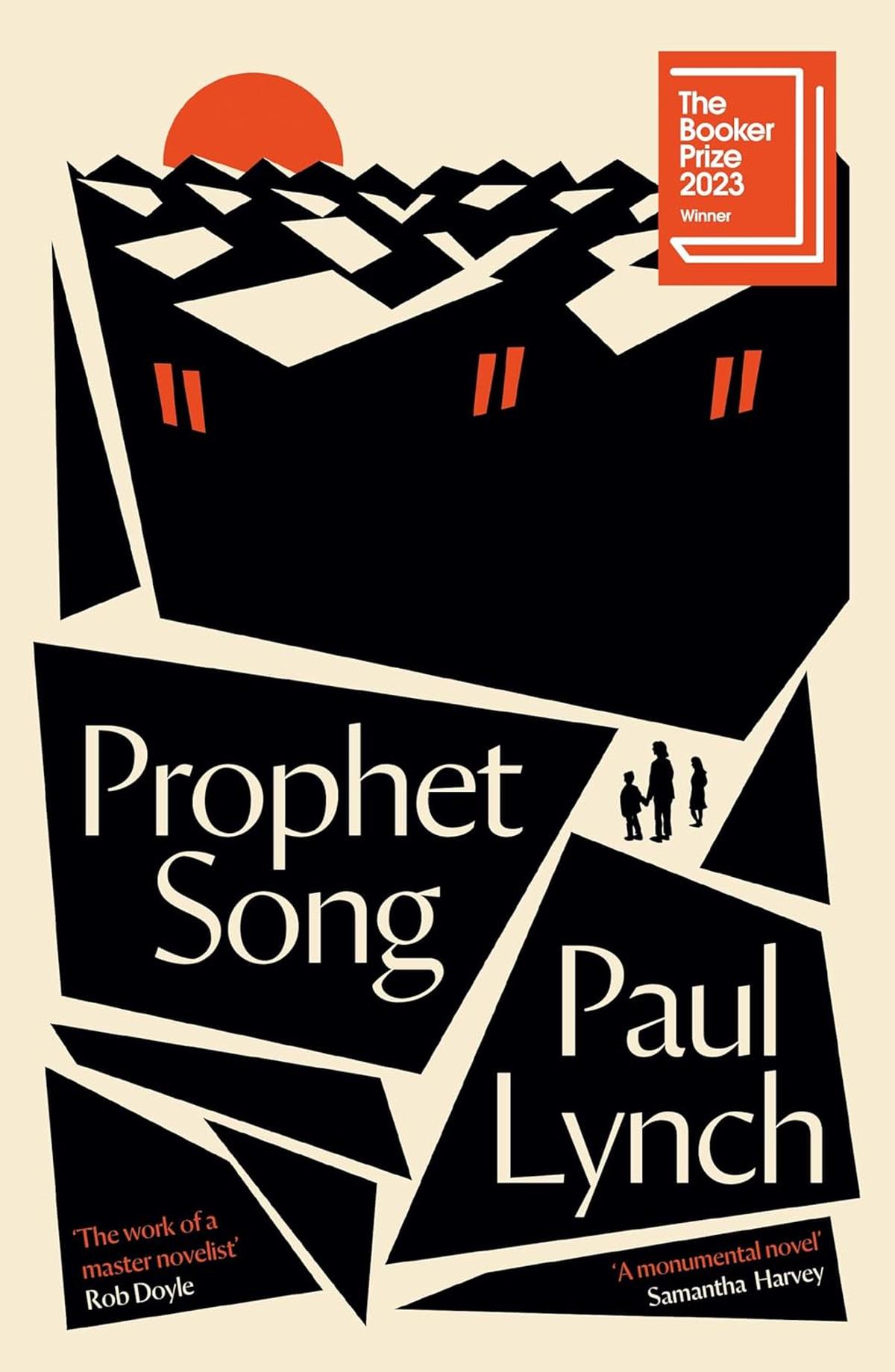

Paul Lynch seems to have lost count of the number of media interviews he has given after he was awarded the 2023 Booker Prize. “I’ve done over 200… way more than 200,” murmurs the Dublin-based novelist, whose prize-winning novel Prophet Song, set in an Ireland that is slowly sliding into the morass of totalitarianism, was aptly described by the Canadian novelist and judging chair, Esi Edugyan, as “soul-shattering and true”.

Lynch, one of the speakers at the recently concluded Kerala Literature Festival in Kozhikode, is clearly itching to return to his desk. “Sooner or later, every winner of the prize of the magnitude of the Booker has to decide what kind of person they are, whether you’re a public-facing person or a writer again,” he says, squatting on concrete so hot that it threatens to slough flesh off bone, the only quiet corner we can find as the colourful chaos of the festival unfurls around us. “And I’ve made the decision to go back to writing… this is one of the only big trips I’m doing this year,” he says with a smile, the shimmer of the Arabian Sea, just a few yards away, reflecting on his dark glasses.

There is something oddly apt about talking to Lynch, now 47, with the ocean so close to us, embodying the primordiality and agelessness of some of the ideas explored in the “mythic novel” that Prophet Song is. “In all my fiction, in all five novels, I’ve always tried to drill down to essential human experience, to get very close to human truths, the things that define what it is to be a human being throughout the ages,” he says. Edited extracts from the interview:

This novel is often referred to as one that captures today’s zeitgeist, given the sort of unrest we’ve been constantly encountering, most recently in Gaza and Ukraine. But it is also a story about the human condition.

I totally agree with that reading. Prophet Song, in many ways, feels like lightning in a bottle, considering the moment that we’re in. But that was not my goal. My goal was to articulate a particular aspect of the human condition, which is what we do to ourselves again and again.

There is this myth of progress, particularly in the West, that we’re always moving in this direct line towards some sort of utopian ideal. We’re not capable of that. Utopia is a dangerous idea because it relies entirely on reason to get you there. And reason is never truly reason in itself; it is always corrupted by belief. Human beings aren’t capable of pure reason.

I was very invested in the character Eilish Stack, and was rooting for her to get out, but she took her time with it. Could we talk about her absolute faith in the idea of a liberal democracy?

One of the chief problems of being alive in liberal democracies is that most of us have come of age entirely within that structure. So, the conditioning is that we always assume it’s going to last. But why should it?

We’re seeing, right now, a massive disruption to the idea of what a liberal democracy is. In Prophet Song, it goes back to the proverbial frog in the pot of water. We know scientifically that the frog does jump out, but symbolically, human beings do not because changes are always slow and very rarely dramatic. We always rely on the fallacy that common sense is going to prevail… The idea of just becoming a refugee, the idea of getting into a boat… these are extraordinarily difficult things to do. Leaving home is the hardest thing to do in the world. The idea of this book was to demonstrate the complexity of this.

People at a vigil in remembrance of Syrian child refugee Alan Kurdi in Melbourne, 2015.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

One of the most emblematic images of the refugee crisis is the 2015 photograph of the little Syrian boy washed up on a Turkish beach. I couldn’t help but think of that photograph when I read this book because that image changed the way we think about refugees. Can you tell us more about the idea of “radical empathy” that you hope this novel will awaken in its readers?

Alan Kurdi was the kid’s name. I remember him on the news. I’m a dad; I’ve got two kids. I remember feeling a certain degree of sympathy, but not enough. And it’s that aspect of ‘not enough’ that I was interested in. Why am I not moved by this?

We are inured against the spectacle that we get every day in our lives. It’s not natural to have war beamed into your sitting room. And so we put this high wall up around our feelings. And I think it’s possibly necessary because how can one individual take on the world’s suffering? But at the same time, as a society, there are questions we have to ask ourselves about the humanitarian aspects of what we’re seeing.

The sentences [in Prophet Song] are designed to get you deeper than what you see on your news or your Instagram feed. Fiction can do something really special. It’s that whisper in the ear that the novelist has. No other art form can do that in the way that fiction can do it. You take the reader into that lived space where empathy, real serious empathy, is possible because you start to feel the pain for yourself.

Could you talk a little about how time and memory work in this novel, how the mundane little moments of our lives acquire such poignancy when it is in danger of being lost.

We’re always the moment of our memory. And our memory is our life. Prophet Song demonstrates that something as catastrophic as this story takes place in slow time, the small moments. It’s in the interactions with your children. It’s in the moments of reflection where you are just lost in your thoughts and have these moments of being in the world.

My writing seeks to locate the full consciousness of the individual within the grand scale. I’m looking for this particular type of scalability where I can capture the enormity of events but also the preciousness of the tiny moment and place that all within the same sentence. It’s kind of a crazy thing to do. (laughs)

preeti.zachariah@thehindu.co.in

Published – January 30, 2025 04:22 pm IST

![Best Weight Loss Supplements [2022-23] New Reports!](https://technologytangle.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/p1-1170962-1670840878.png)