New diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) were announced recently by the International Working Group (IWG) at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference in Madrid, Spain. A significant change in these diagnostic recommendations, published in JAMA Neurology, is defining the disease as a clinical-biological entity where diagnosis takes into account both the clinical presentation of the disease along with positive amyloid and tau biomarkers—hallmarks of AD pathology.

“The recommendations of the IWG that are published today advocate for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease as being one that is established clinically with support from biomarkers which reflect disease pathology,” said Howard Feldman, MD, a professor of neurosciences at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). “We consider that on their own these biomarkers reflect varying levels of risk of developing disease in people without clinical symptoms.”

The IWG is led by Bruno Dubois and Nicolas Villain from Hôpital universitaire Pitié-Salpêtrière-Sorbonne Université in Paris, along with Feldman and Giovanni Frisoni from Hôpitaux universitaires de Genève in Switzerland. It convened 46 experts from 17 countries to review the role of biomarkers in AD diagnosis with the aim of developing methods to ensure a more accurate and timely diagnosis, particularly in the early stages of AD.

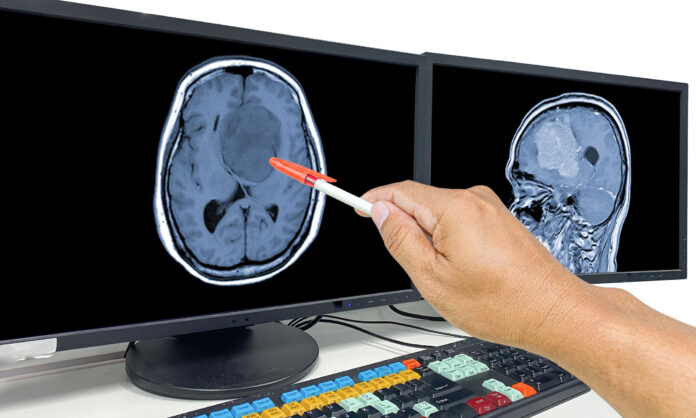

The revised criteria should help enable clinicians to make Alzheimer’s diagnoses at an earlier stage, with an eye toward diagnosis at the prodromal stage, once mild early cognitive decline symptoms are observed, well before full symptoms are apparent.

For individuals who are cognitively normal but show positive biomarkers for amyloid, the IWG recommends the term “Asymptomatic at risk of Alzheimer’s disease.” These individuals have an increased lifetime risk of developing Alzheimer’s but are not yet symptomatic. In contrast, those with genetic mutations—such as autosomal dominant mutations or Down syndrome, or distinct biomarker profiles—are categorized under “Presymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease,” indicating they are at extremely high risk of developing AD.

These recommendations highlight the distinction between people with typical Alzheimer’s symptoms who can be diagnosed with the disease, and those with positive biomarkers but no symptoms, who are considered at risk. This more nuanced approach aims to avoid unnecessary diagnoses and the potential negative psychological impacts of labeling asymptomatic individuals as having Alzheimer’s.

While the IWG supports the integration of biomarkers into diagnosis, it also cautions against over-diagnosing people based solely on biological markers. This puts it at odds with the Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup’s recent revision, which suggests diagnosing Alzheimer’s in cognitively normal individuals with only one core biomarker. The IWG noted their belief that this could lead to false positives, with individuals potentially living with a diagnosis for which they may never develop symptoms.

“As our understanding of Alzheimer’s disease evolves, the advancements in biomarkers are allowing for earlier diagnosis, even before symptoms appear,” noted Villain, a lecturer in neurology at Sorbonne University. “However, it’s crucial to emphasize that our main focus should be on the potential future risks of cognitive decline associated with these biomarkers, rather than just the biological changes themselves.”

The IWG noted that ongoing research into more refined diagnosis of AD could lead to a better understand of how to evaluate the risk of disease development as well as identifying strategies to mitigate these risks through clinical intervention.