Never go back. Manchester City have proof a cliché often contains a certain truth. Comebacks can be savoured at the start and regretted before the end. Paul Dickov was one of their most iconic players of their wilderness years and scored arguably their most important ever goal in the lower leagues. But in his second spell at City, he didn’t score at all. Malcolm Allison was charismatic and catalytic as Joe Mercer’s assistant, albeit less successful when in charge. But when he returned as manager, he broke the British transfer record on the undistinguished Steve Daley and left with them still winless in the league that season when sacked in October 1980.

Yet that was the City of old. When a beloved figure from a more recent past returned, it seemed a prelude to further success. “It feels like returning home,” said Ilkay Gundogan in August; a man whose Manchester home makes him neighbours with Pep Guardiola, who had raised the notion of a transfer himself in one of their regular phone calls during the year they were separated. It seemed a no-brainer, the easiest transfer coup ever pulled off.

Relatively few criticisms could be levelled at City last season – certainly compared to this – but it often felt they were missing Gundogan. Four months into his return, they still are: they could do with the treble-winning captain Gundogan, the big-game player Gundogan, the midfielder who scored crucial goals, knitted games together and could make everything work seamlessly. The Gundogan who could be a defensive midfielder or an attacking midfielder, depending upon the need, would have been invaluable. But that Gundogan is gone. He did not come back.

And after the perfect goodbye came the awkward return. In Gundogan’s last three games of his first spell at City, he lifted three trophies, scored twice in the FA Cup final and got his hands on their first-ever Champions League. In the last three of his second stint, there have been chastening defeats to Tottenham and Liverpool, with City overrun in midfield, with the former skipper cruelly poor, bookended by the draw with Feyenoord when Gundogan scored one goal, helped make another and showed he still has the technique; but his substitution at 3-0 up was a different kind of indication he no longer has the physique. An attempt to spare his 34-year-old legs backfired.

In the happy glow of his August return, the German said: “Not so much has changed”. Sadly for City, it feels as if everything has. Particularly in Gundogan’s sphere of influence. The centre of midfield tends to be the strongest department of any Guardiola side. It looks like the weakest in this team as they have been beaten six times in seven games. And if much of that stems from Rodri’s absence, the reality is that Gundogan has not been able to compensate for it. If it was telling that Mateo Kovacic was the first choice to stand in at the base of midfield, Gundogan seems still less suited. Two thirty-somethings have common denominators: they leave City too open to the quick break, too likely to be overpowered, too vulnerable when there is space.

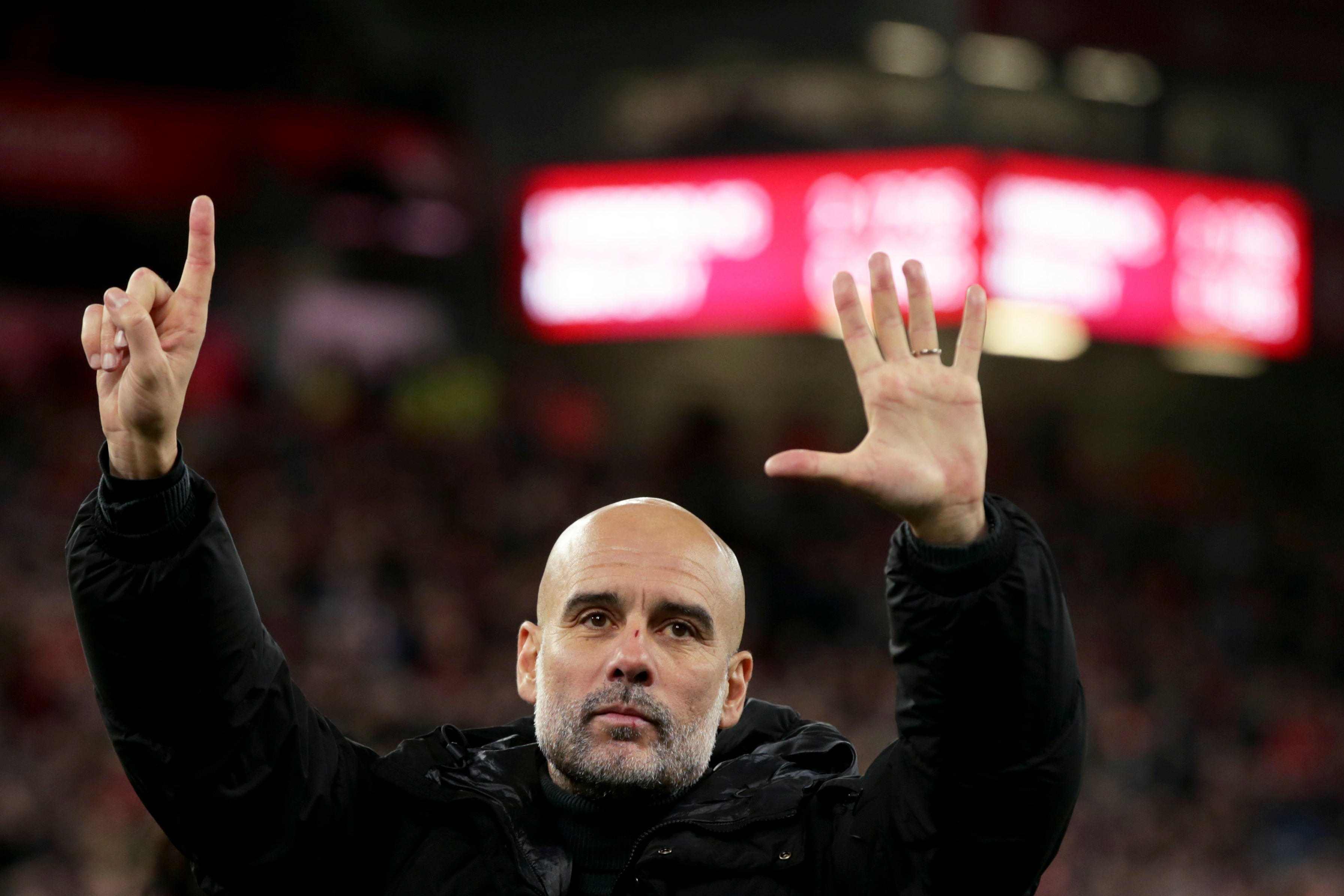

Guardiola has not been blinded to their problems. At Anfield, he admitted: “We don’t have the pace in the middle right now and they are stronger in the duels and you have to survive with the ball. We’re not good in transitions over 30-40 metres compared to them.” Every word of it could have been applied to Gundogan personally. That midfield failing cannot be fixed without Rodri: it renders the veteran the wrong player to have in front of the back four.

There are knock-on effects, too. Maybe getting Gundogan stopped City from pursuing younger midfield targets in the summer. At Liverpool, Guardiola fielded the most defensive possible duo of wide midfielders, in Rico Lewis and Matheus Nunes, as if it would make up for a weakness in the middle. It didn’t.

Then there is the question of the other ageing great in the City midfield. They were staples of a brilliant side two years ago, but it can appear as if Guardiola thinks Gundogan and Kevin de Bruyne are too immobile to both be on the pitch at the same time. They have started together once this season; if that reflects the Belgian’s two-month injury absence, since his return he normally has to wait for Gundogan to come off before he comes on and they have only been paired when City were desperate: 3-1 down to Sporting CP, 3-0 down to Tottenham. Both scorelines duly got worse.

Meanwhile, Bernardo Silva looks increasingly bedraggled from being overworked. If City did not expect Gundogan to play as often on his return, the thought is they have been taken aback by his physical decline. He was never an athlete, but he did have enough running power; except, tellingly, in the games when he was isolated as a holding midfielder when City were caught on the counter-attack.

A year in Spain has blunted his physicality. It renders his 2023 contract talks in a different light: Gundogan wanted a three-year deal, which Barcelona granted him. City now have the worst of various worlds; they didn’t benefit from Gundogan’s presence for his best season since then, but have him now. And re-signing a player of his age has made their rebuilding job bigger.

Such details do not seem to have escaped Guardiola. In the last two weeks, he has talked of a “rebuild”, mentioned that City have 12 players aged 29 or over, lamented how few they have who are 26, 27 or 28 and, at Anfield, talked of going there “in our prime”.

It is now safe to say Gundogan’s prime is in the past. He acquitted himself well at Barcelona last season, but his career peaked when he lifted the Champions League trophy. It was his last act as a City player. Until the comeback gone wrong. “It’s such a joy to be back,” Gundogan said in August. For him and for City, it really doesn’t feel that way now.