- New research suggests a possible connection between ultra-processed foods, stroke, and cognitive decline.

- Ultra-processed foods include chips and many frozen meals.

- Experts say that the next step is further research to explain this connection more deeply and determine which foods create the most risk.

New research published in the journal Neurology is reporting an association between regularly eating ultra-processed foods and the risk of cognitive decline as well as stroke.

The study was based on data across two cohorts, 14,175 in a cognitive decline group and 20,243 in a stroke group. All of the study participants were 45 years old or older.

Dr. Gary Small, the chair of psychiatry at Hackensack Meridian Health and a former longtime faculty member at the University of California Los Angeles, said that the research isn’t surprising from a brain health perspective.

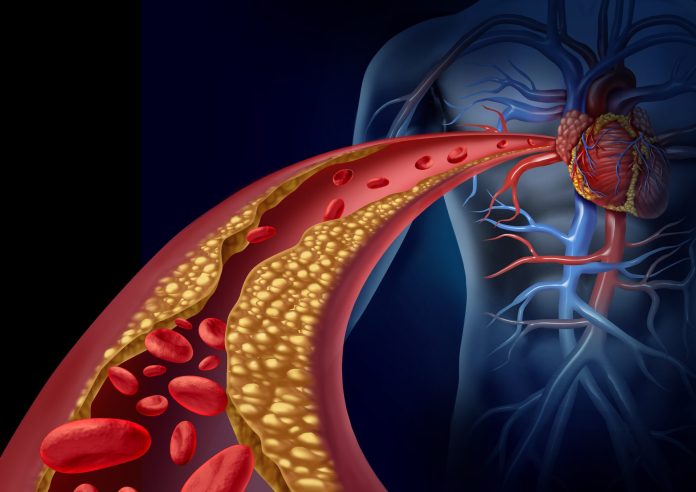

“We know that certain kinds of foods, particularly processed foods, and especially ultra processed foods are not good for your heart. But they’re also not good for your brain,” Small, who wasn’t involved in the study, told Healthline.

Once researchers had determined the role other factors such as age and blood pressure had to play, they reported that a 10% bump in the quantity of ultra-processed foods reported by participants could be associated with a 16% higher risk of cognitive impairment.

When it came to stroke, those who ate more ultra-processed foods had an 8% higher risk of stroke. That risk decreased by 9% for those who ingested more unprocessed or minimally processed foods. Some examples of minimally processed foods include fruits and beans. In studies like these, foods are separated into four groups, using a system called NOVA.

Dr. W. Taylor Kimberly, one of the researchers involved, said these findings have important implications for further research.

“While a healthy diet is important in maintaining brain health among older adults, the most important dietary choices for your brain remain unclear,” Kimberly said in a statement. “We found that increased consumption of ultra-processed foods was associated with a higher risk of both stroke and cognitive impairment, and the association between ultra-processed foods and stroke was greater among Black participants.”

The increase in risk of stroke for Black participants was 15%.

The study used multiple memory assessments and some participants were part of an in-home interview. Those who self-reported having dementia as well as participants who had dementia or depression symptoms or had experience with head injuries were excluded.

Over the course of the 11 years of study follow-up, there were 1,108 strokes reported and 768 cases of cognitive impairment.

In assessing the food consumption of participants, the researchers used a food questionnaire. A score was also calculated that connected the food habits of participants with a number of stroke and neurological function-focused diets. These included the Mediterranean diet, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), and the Mediterranean-DASH intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay.

Dr. Clifford Segil, a neurologist at Providence Saint John’s Health Center in California who wasn’t involved in the study, said he hopes this research can lead to a better understanding of how a diet heavy in ultra-processed foods can impact those with different forms of dementia.

“I would like this group of researchers to team up with a cognitive behavioral neurologist or a neurologist who specializes in diagnosing and treating patients with memory loss to take out a group of the stroke and cognitive impairment patients to determine if eating ultra-processed foods is linked to an increase in vascular dementia or multi-infarct dementia,” Segil told Healthline.

The researchers themselves, including Kimberly, point to the need for further studies in order to connect the dots.

“Our findings show that the degree of food processing plays an important role in overall brain health,” Kimberly said. “More research is needed to confirm these results and to better understand which food or processing components contribute most to these effects.”

Small agrees with the researchers that studying the possible link between dietary choices, stroke, and cognitive impairment can prove difficult, especially when it comes to conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.

“If you follow people to autopsy and you look at their brains, more often than not, it’s not just Alzheimer’s disease,” he said. “They have these mini-strokes in their brain. They may have evidence of head trauma. So, there’s a lot of things that can go wrong with the brain, the positive side with stroke disease there’s a lot you can do to mitigate against it.”

The

Small says that there’s good news in connection to this study that people can implement while they await results of future studies.

“Look, if you live a brain-healthy lifestyle, it’s going to help your heart, it is going to help many aspects of your health,” he said. “I’m not going to wait 20 years to see the definitive study because there’s so much evidence that suggests it’s good for your health, it’s good for your mood. I can just go on and on how important it is for quality of life. You’re going to feel better now about yourself. And live better longer.”