A new study from City of Hope researchers suggests that a high-fiber diet may help reduce the risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and myeloma in patients who undergo bone marrow or stem cell transplants for blood cancer. The study, presented at the 2024 American Society of Hematology (ASH) annual meeting, details how dietary fiber supports a healthy gut microbiome, which in turn may improve overall survival and reduce complications following bone marrow and stem cell transplants.

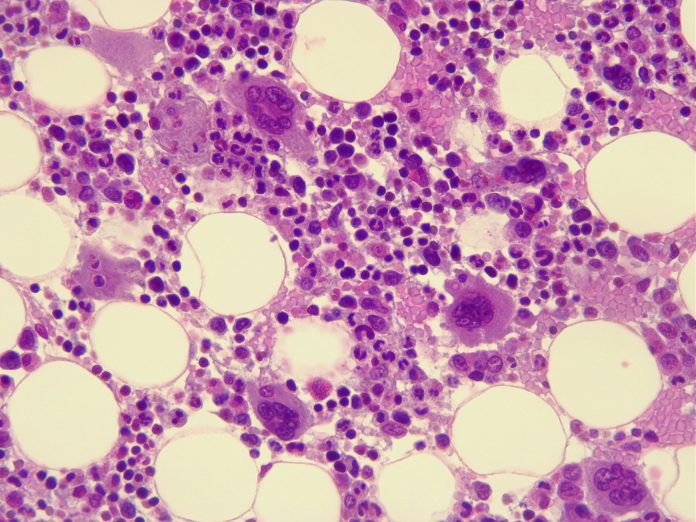

GVHD is the most common adverse event related to a person with blood cancer receiving a bone marrow or stem cell transplant from a donor. These reactions, when the donated cells attack the patient’s own tissue can range from mild to life-threatening.

Currently, patients with GVHD, which presents similar to patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and a depleted immune system are often advised to avoid eating raw vegetables, strawberries, blueberries and other fruits with a removable peel for 40 days post transplantation. This low-fiber diet that includes more cooked foods can help reduce a patient’s exposure to harmful bacteria and reduce symptoms. However, this new research from City of Hope could turn these recommendations on their head.

“We’ve known that dietary fiber plays a beneficial role regulating the immune system via the gut in healthy populations,” said lead author Jenny Paredes, PhD, a staff scientist at City of Hope. “Our work now shows this may be true for transplant patients, too, and that dietary restrictions post-procedure that might result in low fiber intake could be counterproductive.”

The research team analyzed the diets of 173 transplant patients, from 10 days before to 30 days after their procedures, and found that patients who consumed higher amounts of fiber had a reduced risk of developing acute GVHD, in the lower gastrointestinal tract and better overall survival. A low-fiber diet was linked to a less diverse gut microbiome, which can leave patients more vulnerable to infection.

Significantly, higher fiber intake was associated with higher levels of butyrate-producing gut microbes. Previous research has shown that butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid produced when fiber is fermented by the gut microbiota, protects against GVHD.

To further investigate these mechanisms, the team conducted a preclinical study in mouse models of GVHD. Mice that were fed a high-fiber diet rich in cellulose exhibited a significant reduction in GVHD-related deaths and improved overall health. These mice also had increased microbial diversity and higher concentrations of butyrate in their guts, similar to what had been observed in humans.

“While high-fiber diets may not be appropriate for everyone, this study shows the exciting potential for high fiber to play a role in reducing GVHD risk in transplant patients,” Paredes said. “We look forward to designing a nutritional intervention for clinics that can help diversify the gut microbiome through food choice and improve outcomes for people receiving bone marrow or stem cell transplants.”

The study was conducted in collaboration with the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and was supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute and private foundations.