The news hasn’t been good for people planning to live for ever. First came Dr Saul Newman’s investigative work into supercententarians – those aged 110 or older. In a paper titled “Supercentenarian and remarkable age records exhibit patterns indicative of clerical errors and pension fraud”, Newman reported that high concentrations of supposedly extremely old people occurred, implausibly, in places with the highest rates of poverty – a predictor of the worst health – and with no birth certificates. In the US, the number of supercentenarians declined by between 69% and 82%, depending on the state, when birth certificates were introduced.

Guttingly for anyone who spends a fortune on jasmine tea and nattō by following the Okinawa diet, Newman’s research also challenged the notion of “blue zones”, pointing to high error and fraud rates in those mythic, much-admired areas with high concentrations of centenarians. In 2010, more than 230,000 Japanese centenarians turned out to be missing, imaginary, clerical errors or dead; in Greece, 72% of census-reported centenarians in 2012 were discovered to be dead (“or, depending on your perspective, committing pension fraud”). Dump the daikon! Banish Greek beans! (Not really: they are still good for you, just not “live to 120” good.)

But we will still live longer than our grandparents, won’t we? About that: we may be reaching peak longevity. New research analysing international demographic data suggests the “limited lifespan hypothesis” (which posits that we are nearing the upper limit of human lifespan) may be correct. There is, apparently, “no evidence to support the suggestion that most newborns today will live to age 100”. “We’re suggesting that as long as we live now is about as long as we’re going to live,” the study lead, S Jay Olshansky, told the New York Times.

On first blush, that seems disappointing, especially the super-old probably not being as old as previously thought, or indeed alive. I always enjoy reading about their boozing, chocolate-scoffing and smoking antics. It must be especially unwelcome for Silicon Valley’s loopy longevity community. “Professional rejuvenation athlete” Bryan Johnson would be livid if he weren’t far too busy masticating his compost heap of a breakfast while wearing an infrared hat to notice (I watched a video of his morning routine recently and instantly lost my own will to live).

But could these longevity bombshells actually be good news, and not just because I feel a spiteful satisfaction imagining that the self-absorbed biohacking billionaires are on a hi-tech hiding to nothing? Accepting that no hack will make us immortal may help us focus on how to make our finite lives better, by tackling our real problems. That includes the one most likely to curtail all our life expectancies: the climate. Even from a purely selfish perspective, why would you want to live to 120 confined to the servants’ quarters of a billionaire’s bunker complex, explaining to your surviving great-grandchild what a bird was as you share out the family ration of worm gruel? And if you are the billionaire in question, what is the appeal of living for ever on a dying planet? How about doing something about it, rather than trying to turn yourself into a (freakishly long-lived) naked mole rat?

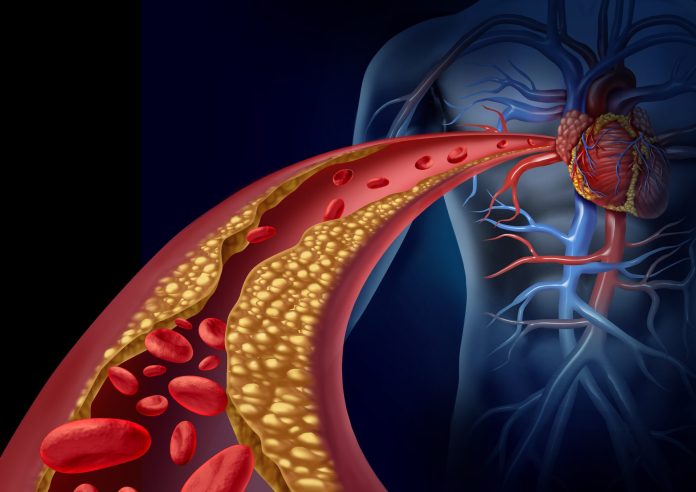

It might help us focus on quality, not quantity, too – something we are struggling with. New UK research indicates today’s 50- to 70-year-olds are at greater risk of chronic illness and disability than their predecessors, with rising rates of cancer, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. That is mind-boggling, given all the medical advances of the postwar period. “These worrying trends may see younger generations spending more years in poor health and living with disability,” said the study’s lead, Laura Gimeno.

In addition, research last year reported that one in five adults over 65 in England feels lonely, a state that itself frequently leads to poor physical and mental health. England isn’t special in this: with an ageing, atomised population, 68,000 people are expected to die in Japan’s chilling “lonely death epidemic” this year.

We don’t want to die, but we have allowed our world to become a place in which ageing is an unappealing, even frightening, prospect. Perhaps we could do better if we focused our energies on ensuring everyone gets to be here for a good time, not a (very) long time?

![Best Weight Loss Supplements [2022-23] New Reports!](https://technologytangle.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/p1-1170962-1670840878.png)