This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Justin L. Berk, MD, MPH, MBA: Welcome back to The Cribsiders. This is one of our Medscape video recap summaries of a podcast episode that you can check out online.

Jessica Hane, MD: Justin, what topic are we reviewing today?

Berk: Fatty liver disease — NAFLD, NASH, whatever you want to call it. We’re talking about when the liver hepatocytes are overrun with fat. We had a great conversation with Dr Rohit Kohli, chief of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Children’s Hospital, Los Angeles. We talked about identification strategies, management tips, and lifestyle-changing advice to be able to share with your patients.

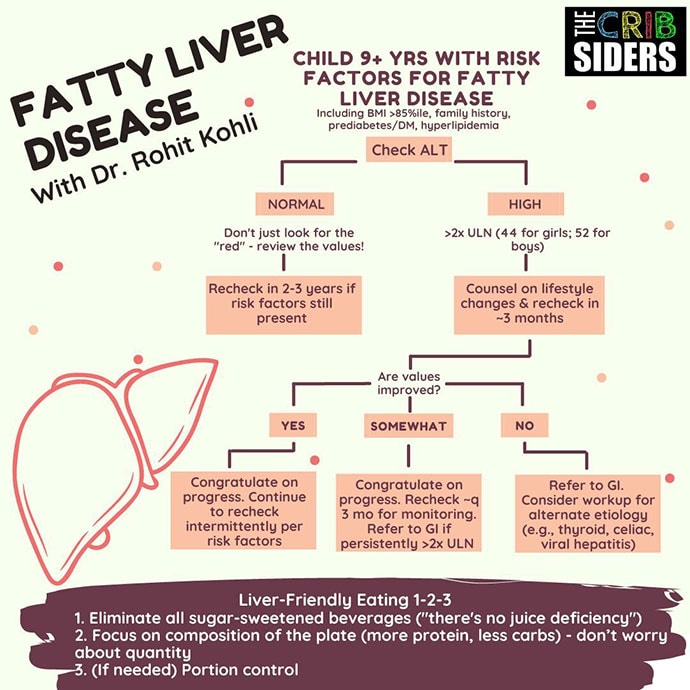

Hane: Question number one is, who should get screened?

Berk: Essentially, the guidelines say that you should check an ALT level in children aged 9-11 years if their BMI percentile is greater than 95% or between 85% and 95%. But there are additional risk factors such as central adiposity, insulin resistance, prediabetes, diabetes, dyslipidemia, sleep apnea, or a family history of NAFLD. These are the higher-risk patients who should be screened.

Hane: So when we get these labs, what are we actually looking for?

Berk: It’s actually pretty simple. The number-one way to screen for NAFLD is with an ALT level, which is most specific to the liver. Some clinicians use the GGT, but ALT is what most of the guidelines say. If the ALT is two times the upper limit of normal, we should start regularly checking liver function and identifying patients at high risk for NAFLD. An ALT of 80 is the magic number, in combination with elevated BMI. These patients are a bit more concerning — and may even need a referral to gastroenterology to be aggressive right from the start.

Hane: For patients with elevated ALT levels, should we be considering other diagnoses?

Berk: This is a great question. We find a patient with an elevated BMI. We do the ALT to screen for NAFLD and it’s elevated. Does this mean that they absolutely have NAFLD? Not quite. We can try lifestyle management, and if that doesn’t work (no weight loss, no improvement in the ALT level), then we should start thinking about a secondary workup to rule out other etiologies — for example, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, autoimmune hepatitis, celiac disease, or thyroid disease. Our guest emphasized that not every patient with an elevated BMI and an elevated ALT has NAFLD. The NASPGHAN guidelines — the pediatric GI society — has a good list of other tests to consider.

Hane: Can imaging help stage the disease process?

Berk: That’s exactly right, Jessica. Imaging is the core way to figure out disease severity because it can help determine whether there’s fibrosis. The imaging modality is looking for stiffness, so ultrasound is not helpful. Instead, you need vibration-controlled transient elastography, like a FibroScan or magnetic resonance elastography (MRE). These modalities can find and stage fibrosis. Biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosing and monitoring the progression of NAFLD.

Hane: How do we counsel patients with elevated ALT levels to protect their liver?

Berk: This is a big component of the lifestyle approach. One of the first steps that our expert guest suggested was getting rid of sugar-sweetened beverages. That’s low-hanging fruit. His jingle is “if it’s sweet and you can pour, kick it out the door.” He tells families there is no juice deficiency in their child — we don’t need to supplement with juice. Let’s focus on getting rid of those sugar-sweetened beverages.

If that’s not enough, focus on the composition of the plate — more protein, fewer carbs — and not really focusing on quantity or portion control yet because of the mental component (we have a great episode about weight-based views of food). Try not to focus on that until you encounter resistance without much improvement.

Hane: So really starting with nutrition, but are there any medications that you can use in kids?

Berk: Nutrition is really the core of treatment. There are no FDA-approved therapies for NAFLD in children. Some evidence supports vitamin E, which has had some meaningful impact. In the clinic, some experts will use vitamin E for patients. Dr Kohli said it can be given to kids with biopsy-confirmed NAFLD, but for no longer than 2 years because there are some concerns about associations with risk for cardiovascular and prostate disease. But fortunately, there are a lot of other ongoing studies, so within 2 years we might have other medications that could really help these patients.

Hane: Final question, Justin: Why is this topic so important?

Berk: My eyes were opened to how much of a public health epidemic NAFLD really is. It’s the most common liver disease in the United States, with a prevalence projected to be about 30%, and rates are increasing — that’s almost 1 in 3 kids who will have some fatty liver disease. Currently, it’s the number-two indication for adult liver transplantation, but there are good estimates that by 2030, it’s going to be the number-one indication for liver transplant. All of this means that we need to be advocating early, and diagnosing NAFLD earlier, because this is becoming a public health emergency. On this episode, we learned a lot of great pearls to try to address this issue.

Hane: Thank you all for joining us for another Medscape video recap of The Cribsiders pediatric podcast. Visit can listen to the full episode, Fatty Liver Disease with Dr Rohit Kohli, at the Cribsiders website.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube