A study led by researchers at the Duke Cancer Institute has uncovered new insights into the role of estrogens in cancer growth, particularly in breast cancers that lack estrogen receptors. The research, published in Science Advances, describes how estrogens not only decrease the ability of the immune system to attack tumors, but also the effectiveness of the immunotherapies used to treat an array of cancers, notably triple-negative breast cancer.

“The treatment for triple-negative breast cancer has been greatly improved with the advent of immunotherapy,” said senior author Donald McDonnell, PhD, the Glaxo Wellcome Professor of Molecular Cancer Biology at Duke University School of medicine. “Developing ways to increase the anti-cancer activity of immunotherapies is a primary goal of our research.” Triple-negative breast cancer is particularly aggressive, characterized by the absence of estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 receptors.

While significant progress has been made in developing new and effective treatments for breast cancer, there is still a substantial need for new approaches that can be used to treat patients whose tumors progress while on standard of care, while also seeking to treat those patients at high risk of disease recurrence.

The Duke investigators, including first author Sandeep Artham, PhD, a senior researcher in pharmacology and cancer biology, conducted a comprehensive analysis combining a retrospective analysis of patient data with experiments in mouse models. Their study revealed that estrogens contribute to tumor growth in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancers and other tumor types, including melanoma and colon cancer.

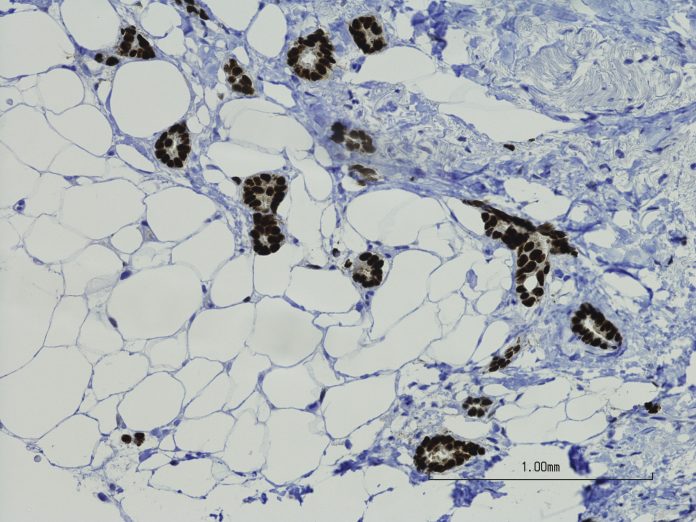

Key to their findings was the impact of estrogens on the immune system. The researchers discovered that estrogens decrease the presence of eosinophils, a type of white blood cell involved in immune responses. An increased number of eosinophils within tumors and tumor-associated tissue eosinophilia (TATE) have been linked to improved patient outcomes in multiple cancers including colon, esophageal, gastric, oral, melanoma and liver cancers. Estrogens have been shown to decrease the number of eosinophils and TATE in mice.

The Duke researchers found that by using anti-estrogen drugs, they could reverse the negative effects of estrogens and restore the immune system’s function against tumors.

“Here we have found a simple way to bolster the effectiveness of immunotherapy for this type of breast cancer and the benefit was even seen in other cancers, including melanoma and colon cancers,” McDonnell said.

The research also highlighted how anti-estrogen therapies inhibited estrogen receptor signaling, which in turn enhanced the effectiveness of immunotherapies. This approach demonstrated slowed tumor growth, offering a potential pathway for improving treatment outcomes for patients with aggressive cancer types.

With the promising results from their studies, the Duke team now plans to conduct clinical trials to evaluate the effectiveness of an investigational anti-estrogen drug called lasofoxifene in patients with triple-negative breast cancers.

The study’s focus on the intersection of estrogen signaling and immune activity may open new avenues for treatment, particularly for those with aggressive forms of cancer.

“These findings establish the importance of ER (estrogen receptor) signaling in eosinophils on tumor pathobiology and highlight the potential utility of combining ER modulators…with (immune checkpoint blockades) in patients with breast cancer and other cancers where the presence of TATE is beneficial,” the researchers concluded.