Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a prevalent neurodevelopmental condition in childhood, affecting approximately 4-6% of children and adolescents [1]. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) includes ADHD under “Neurodevelopmental Disorders” [1]. ADHD is defined as six or more symptoms of persistent inattention, and/or hyperactivity, and impulsivity, present for six months in two or more settings that interfere with function and are inappropriate for developmental level [2]. Children and adolescents diagnosed with this disorder have difficulty focusing, controlling movements and impulses, and regulating behavior affecting their communication, daily living, and socialization [3].

Boys are two to four times more likely to be diagnosed than girls [4]. In addition, 65% of children diagnosed with ADHD are symptomatic in adulthood, which suggests that the disease is chronic [2]. The etiology of ADHD is multi-factorial and a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental factors, such as low birth weight, prematurity, pregnancy complications, prenatal maternal smoking, intrauterine alcohol exposure, and lead [5]. Family and twin studies have shown a high percentage of heritability with approximately 70% to 80% and substantial overlap between hyperactivity/impulsivity and inattention and with no sex differences in heritability [4]. Although family studies have shown a high heritability and multiple candidate genes that may be involved in the disorder, genome‐wide studies have not yet found a clear association [4].

In addition, over 65% of ADHD patients present with psychiatric comorbidities, including depression, anxiety, and learning disorders, which affect academic performance and family life, with enormous social and economic problems when left untreated [2]. In children younger than six, ADHD is the most common psychiatric reason for referral to a specialist child and adolescent psychiatrist [6]. In addition, parent reports indicate that more than one in ten school-age children (11%, 6.4 million) in the United States have been diagnosed with ADHD by their primary care provider [7].

Clinical practice guidelines recommend a combination of pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for treating ADHD in children and adolescents aged six to eighteen years [7]. The psychostimulant, methylphenidate (MPH), has been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating ADHD and is considered a part of the standard of care [7]. ADHD imposes a significant financial burden on families, healthcare systems, and schools [7]. Children and adolescents with ADHD frequently receive special education services, drop out of school, and achieve a much lower rate of post-high school education than their peers [8]. Also, more than 40% of preschoolers diagnosed with ADHD are at risk of suspension, and about 16% are likely to be expelled from school or daycare, compared to only 0.5% of children without ADHD [6]. Consequently, there have been tremendous efforts to develop pharmacological treatments to improve their quality of life and evaluate CBT; for example, cognitive restructuring, thought-stopping, behavioral activation, and exposure techniques to accomplish behavioral management [8].

Research has shown that pharmacological treatments, particularly stimulants and atomoxetine, psychosocial therapies, and their combination are well-established interventions for children and adolescents with ADHD [8]. Treatment options for ADHD in adolescents and children are limited and primarily require prescribing psychostimulant medication as a first-line treatment [3]. Improvements in behavior, attention, interpersonal interactions, cognition, and executive function reinforce stimulant medication’s short-term efficacy. MPH and dextroamphetamine are the most prescribed [3]. Nevertheless, the limitations of these medicines (e.g., short-term effects, unknown long-term effects, and adverse effects such as insomnia and anorexia) have led parents and professionals to seek other treatments. Therefore, non-pharmacological interventions that decrease ADHD symptomatology, such as cognitive training, have been considered an excellent potential benefit [3].

The primary care provider roles include diagnosis, medication management, and referrals to other resources, both educational and behavioral [9]. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has recently updated its 2019 guidelines, providing the basis for managing ADHD. First-line treatment for the preschool age group four to five years is evidence-based parent training in behavior management (PTBM) and teacher-administered behavioral therapy. If there is no improvement, initiating MPH may be considered. For elementary school-aged children six to eleven years, approved medications by FDA, along with PTBM and classroom behavioral interventions, are preferred. For adolescents aged 12-18, FDA-approved medications are the treatment of choice. Evidence-based training interventions and behavioral interventions should also be encouraged [9].

CBT has been described as “a form of psychological therapy that uses cognitive and behavioral techniques to support individuals to change unhelpful behaviors and thought patterns that occur in situations of fear and to learn better ways of coping with them, thereby relieving their symptoms and becoming more effective in their lives” [9,10]. CBT is delivered in a series of structured sessions and is effective for depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and severe mental illness. Results of two studies of adolescents receiving CBT showed improved parental ratings of ADHD symptoms but found little evidence of benefit for functional impairment [9]. On the other hand, MPH, a dopamine and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor, is the recommended first-line pharmacological treatment for ADHD in many countries, with treatment response rates between 70% and 90%. As stated previously, MPH is one of the most used psychostimulants and has been the most widely studied regarding its efficacy in treating ADHD worldwide [11]. Compliance with medication is a common problem in ADHD treatment. Lack of adherence may lead to reduced effectiveness, increased adverse events, and other consequential issues, hampering the course of pharmacological treatment. Clinicians should routinely assess medication compliance during treatment, and potential problems in adherence should be openly discussed [12]. In deciding whether to initiate pharmacological treatment in school children and adolescents, the severity of ADHD symptoms, as emphasized by clinical guidelines: cases with low and moderate severity “can” while severe cases “should” be offered pharmacological treatment. However, personal factors, for example, the level of suffering, the situation of the patient’s family, comorbidities, and global psychosocial functioning, should also be considered [12].

This review aims to systematically evaluate the effectiveness of MPH and CBT, in treating children and adolescents with ADHD using available literature. The study also establishes the most efficacious treatment in the current period.

Methods

Guidelines

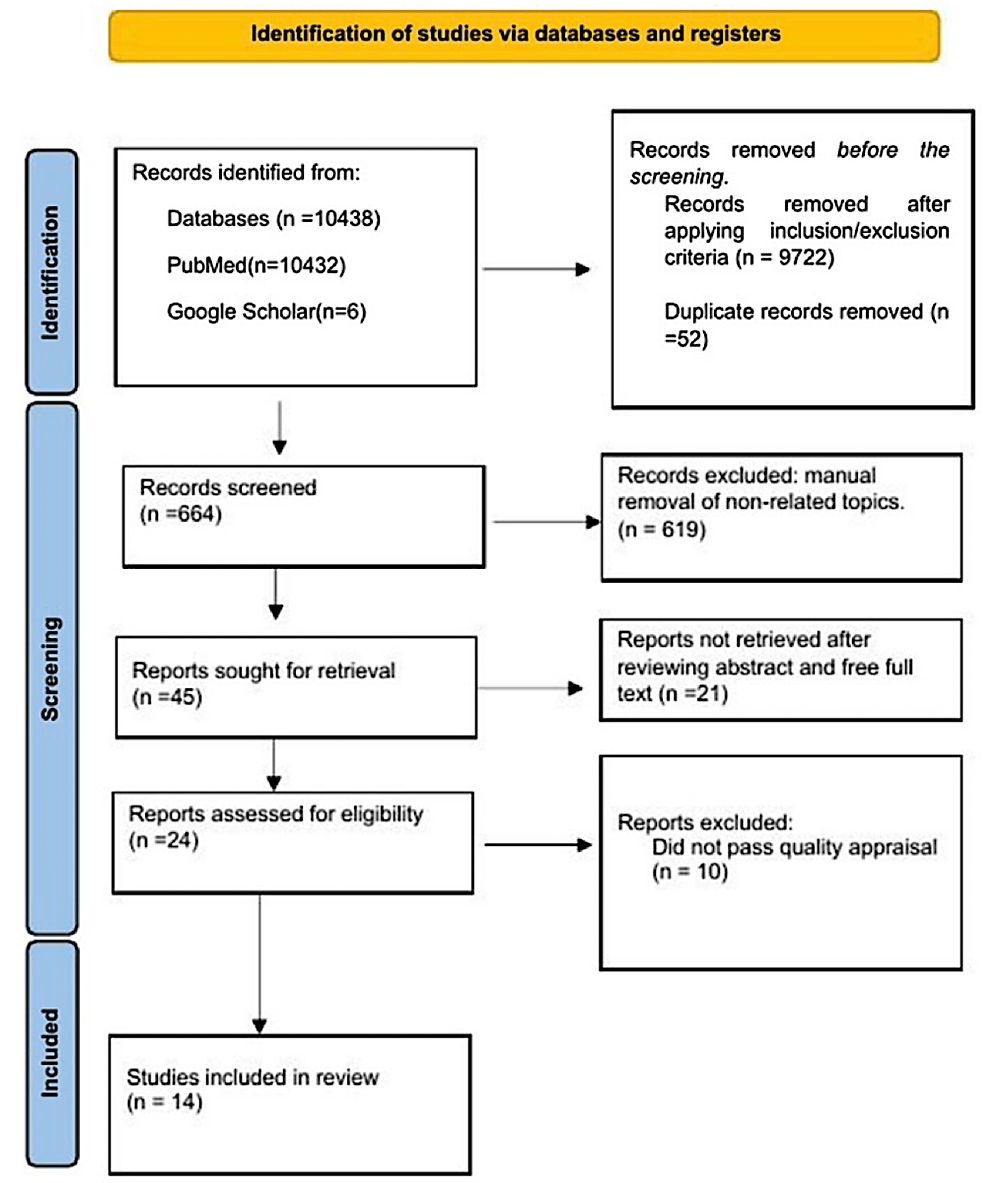

This systematic review of empirical literature was performed in agreement with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 [13].

Search Databases

Three investigators independently searched PubMed, PubMed Central, Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), and Google Scholar.

Search Strategy

A systematic literature search using boolean logic to perform a database search and boolean search operators “AND” and “OR” were used to connect the keywords. PubMed search for free full-text articles, conducted in humans and published in English from 2017 until July 30, 2022, using medical subject headings (MeSH) terms keywords in the MeSH database are as follows Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder OR ADHD OR Hyperkinetic syndrome OR (“Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity/drug therapy” [Majr] OR “Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity/therapy” [Majr]) AND Cognitive behavioral therapy OR Psychotherapy OR Behavioral therapy OR (“Cognitive Behavioral Therapy/methods” [Majr] OR “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy/organization and administration” [Majr] OR “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy/statistics and numerical data” [Majr] OR “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy/trends” [Majr]) AND Methylphenidate OR methylphenidate hydrochloride OR Central nervous system stimulants OR (“Methylphenidate/administration and dosage” [Majr] OR “Methylphenidate/adverse effects” [Majr] OR “Methylphenidate/pharmacology” [Majr] OR “Methylphenidate/therapeutic use” [Majr] OR “Methylphenidate/therapy” [Majr]). We also performed a direct search on Google Scholar using the keywords Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Hyperkinetic Syndrome, Attention Deficit Disorder With Hyperactivity, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), Psychotherapy, Behavioral Therapy, Methylphenidate OR Methylphenidate Hydrochloride, Central Nervous System stimulants, treatment, efficacy, children, and adolescents. The PICO (population, intervention, criteria, outcome) will be outlined (Table 1).

Inclusion Criteria

The papers included in this study are within a range of five years, from 2017 to 2022. Only human studies published in English are part of this study. We included randomized control trials, observational studies, systematic reviews, or narrative reviews, including the age group of preschools to adolescents who received MPH and CBT for treating ADHD.

Exclusion Criteria

In our study, the authors excluded studies published before January 2017, studies that were not free full text on PubMed, studies not published in English, and finally, studies in individuals over 18 years of age. Furthermore, we excluded clinical guidelines and letters to the editor.

Study Selection and Quality Check

The studies we shortlisted were then imported into the EndNote software (Clarivate, London, UK) and transferred to the excel sheet, where we removed duplicates. In addition, we performed a manual check to remove any article to which the topic was non-related. Three reviewers independently reviewed papers based on title, keywords, and abstract. In addition, two reviewers thoroughly reviewed full-text articles that passed the initial screening to determine their suitability for inclusion in the systematic review. The quality of the paper included in the study was assessed by the primary author and two secondary authors using the Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized controlled trials. We interpreted the result from the biases using the agency for healthcare research and quality (AHRQ) standards. Finally, the papers selected were of good quality. Finally, the investigators used the PRISMA diagram to check the quality of systematic reviews for inclusion.

Additionally, we used the scale for assessing narrative review articles (SANRA) checklist to determine if a narrative review was of good quality. Finally, in the event of disagreement, we reached a consensus after discussing it with a fourth author. The PRISMA flow diagram is below in Figure 1 [13].

Results

After a strategic search of various electronic databases, the total number of articles found was 10438 (PubMed – 10432, Google Scholar – six). Records were removed before screening by PubMed filter inclusion criteria = 9722. We removed 52 duplicates with excel. The authors manually screened by title 664 studies and removed 619 articles with a non-related topic. We retrieved 45 records and excluded 21 studies after reviewing abstracts and full text using the eligibility criteria. The investigators identified 24 studies, and 10 did not meet the inclusion criteria after the quality assessment. Finally, we included 14 articles in our review. The PRISMA flow diagram is in the methods section (Figure 1) above. Finally, we outlined the type and number of studies used in this review article (Table 2).

General Study Characteristics

Study participants: The studies included were performed in seven countries; the United States, Taiwan, Norway, Australia, the Netherlands, Denmark, and France [6,7,11,14-24]. The total number of participants recorded was 2,098. The age ranged from 3 to 18 years old, and the mean age observed from the review was 11. However, only one study in this review did not specify the sample size and age range [21]. Therefore, we will explore the essential characteristics of the studies included in this review (Table 3).

Review of Diagnostic Assessment Measures

Two essential treatment modalities, CBT and MPH, were used to assess the primary efficacy outcome: reduced symptoms and improved function in patients with ADHD. The study outcomes were measured using diagnostic assessment measures, which were different in all studies and were undefined in two studies. The “parent symptom rating,” the highest applied diagnostic assessment measure, was used in 11 studies. In contrast, eight studies showed that the “structured-self-rated questionnaire” is the second most used diagnostic assessment measure. The other diagnostic assessment measure, “teacher symptom rating” and “investigators,” the third most utilized, appeared in six studies.

Type of Treatment Considered Dosage and Duration

The authors analyzed the treatment type, dose, duration of therapy, frequency of assessment, and patient response to demonstrate whether the administration of CBT and MPH is effective. One study assessed MPH and CBT in the included articles [18]. Six studies centered on CBT [15-18,23,24], while nine researchers centered on MPH administration [6,7,11,14,18-22]. The dosage of MPH was different in each of the nine studies. In addition, the duration of the interventions ranged from five weeks to four years, while the frequency of assessment varied extensively.

Review Findings

Our findings showed an improvement in core ADHD symptoms. We observed that eight studies recorded a reduction in inattention, and seven reported a decrease in hyperactivity and impulsivity/aggressiveness. Two more studies also reported improvements in the change in symptom scores using the ADHD rating scale and improved working memory. Nonetheless, Sciberras et al. [17] randomized control trial study outcomes were undefined, and Ribeiro et al. [21] didn’t find enough evidence regarding the benefits of MPH on treatment outcomes.

Discussion

A research review, including 11 random controlled trials, two systematic reviews, and one narrative review (Table 2), was used to assess the effects of either CBT or MPH on core ADHD symptoms and function in children and adolescents. This review differs from previously published reviews, intending to focus on the effect of non-pharmacologic therapy (CBT) and stimulant therapy (MPH) as interventions for treating children and adolescents with diagnosed ADHD. In addition, the author’s included the established rating scales used in assessing ADHD symptoms in children, as shown in (Table 4) for better understanding [19].

Several behavioral assessment scales have been specifically designed for this patient population to enable physicians to identify patients with ADHD better while excluding those showing developmentally normal behavior. These include the Conners Parent Rating Scale-Revised (Conners et al. 1998a) and Conners Teacher Rating Scale-Revised (Conners et al. 1998b), the AD/HD Rating Scale-5 parent and teacher versions (DuPaul et al. 2016), the Early Childhood Inventory-4 (Sprafkin et al. 2002), and the Child Behavior Checklist (de la Osa et al. 2016). The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (Egger et al. 2006a) was developed based on the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (Angold and Costello 1995) for children two to five years of age. Still, no validation reports in that population have been published to date. The Vanderbilt ADHD Teacher and Parent Rating Scales have been validated in children aged six to twelve but are also applicable to preschool children (Wolraich et al. 1998, 2003; American Academy of Pediatrics 2019). The Conners scales and AD/HD Rating Scale-5 are specific to ADHD behaviors and based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) ADHD criteria. In contrast, the Child Behavior Checklist and Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment assess a wide range of behaviors and do not reflect criteria for ADHD alone (Conners et al. 1998a, 1998b; Egger et al. 2006a; de la Osa et al. 2016; DuPaul et al. 2016). Physicians must remain cautious in diagnosing ADHD in preschool children, monitoring very young children for the emergence of symptoms and impairments over time [19].

CBT Intervention

The CBT interventions in six studies included in this review had different measures of assessing the effectiveness of the ADHD treatment [15-18,23,24]. The study observed that CBT improved ADHD symptoms (Table 3). However, CBT can be time-limited and resource-intensive. The variations in CBT treatments could be the mode and duration of CBT sessions. Most studies had weekly clinician-led sessions, and the number of sessions varied. The duration of each session also varied between studies lasting an hour long and beyond, and the sessions can be either with individual children/parents [17] or combined [24]. Finally, we will detail the CBT sessions reviewed in our study (Table 5).

MPH Treatment

The nine studies included in this review have different formulations of MPH [6,7,11,14,18-22]. Since the advent of MPH in the 1960s, MPH has been the drug of choice for ADHD worldwide and has proven to improve ADHD core symptoms. Pharmacological treatment optimization poses challenges, including careful dose adjustments and the risk of drug abuse during treatment [14]. The study reported marked improvement in ADHD core symptoms six months after treatment completion by parents, teachers, and participants, with significant improvement in inattention [14]. However, the study did not witness a significant improvement in hyperactivity or academic performance [14]. Furthermore, treatment with MPH ERCT (extended-release chewable tablet) showed a significant improvement in ADHD symptoms compared with placebo at two to eight hours post-dose, with a good safety and tolerability profile [7]. In the first multicenter, phase three study of the efficacy and safety of MPH ERCT formulations, the results showed a statistically significant improvement in behavior impairment in children aged six to twelve with ADHD [7].

Additionally, in the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial of an ER MPH formulation for preschool children aged four to six years, doses of up to 40 mg were effective and well tolerated [6]. It is like the known safety profile in older children [6]. Another study, a placebo-controlled crossover trial looking into the clinical efficacy and tolerability of ORADUR-MPH, reported that it significantly reduced symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity within two weeks of treatment regardless of informants [11]. ORADUR-MPH is efficacious, safe, and well-tolerated for treating ADHD without serious side effects [11].

Limitations

This study has some critical limitations. The major one is the limited number of articles documenting the use of MPH and CBT alone to treat ADHD. Furthermore, a systematic, non-descriptive review of CBT sessions was included [15] and provided limited measures for the discussion. In addition, we included an unresolved research protocol, which can be controversial due to the lack of an evident result. Some studies lacked information on the study characteristics, and we did not contact the authors. This insufficiency in knowledge may have affected the quality of the outcome of the result. Also, our studies used different CBT session approaches and varying formulations and dosages for MPH; therefore, this needs to be considered for overt improvement.

Finally, our search strategy excluded studies published before the last five years and not freely available full text on PubMed. The inclusion of these might have provided more clarity.

![Best Weight Loss Supplements [2022-23] New Reports!](https://technologytangle.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/p1-1170962-1670840878.png)