India’s reservation system has long been a tool for uplifting historically marginalised communities, particularly the Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs). Born out of the need to correct centuries of social and economic exclusion, reservations have opened the doors of higher education, government employment, and public offices for groups once condemned to the periphery of society. Yet, over 75 years since independence, questions are being raised about whether the system is serving its intended purpose — especially when some subgroups within the SCs appear to be benefiting more than others.

Recent debates, spurred by a Supreme Court ruling, have questioned whether a ‘quota-within-quota’ system is needed to ensure that affirmative action policies are more equitable across SC subgroups. The idea is to subdivide the SC quota to provide targeted assistance to the most disadvantaged communities within the broader SC category. While some States, like Punjab, have experimented with such policies, the effectiveness of subdividing quotas is still a matter of contention.

The question at the heart of this debate is: do all SCs benefit equally from reservations? And if not, should the system be redesigned to ensure a more balanced distribution of opportunities?

A deep dive into caste quotas

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the principal architect of the Indian Constitution, believed that formal legal equality (one person, one vote) would not be enough to dismantle the deeply entrenched inequalities of caste. Thus, reservations were mandated to become a mechanism to move from legal equality to substantive equality by creating opportunities for SCs and STs in higher education, public sector jobs, and government institutions.

The argument underlying the Supreme Court verdict is that despite its progressive aims, India’s reservation system is plagued by uneven outcomes. Some SC groups seem to have progressed more than others over the decades. This has led to calls for a more nuanced approach to affirmative action — one that recognises the heterogeneity within the SC category itself.

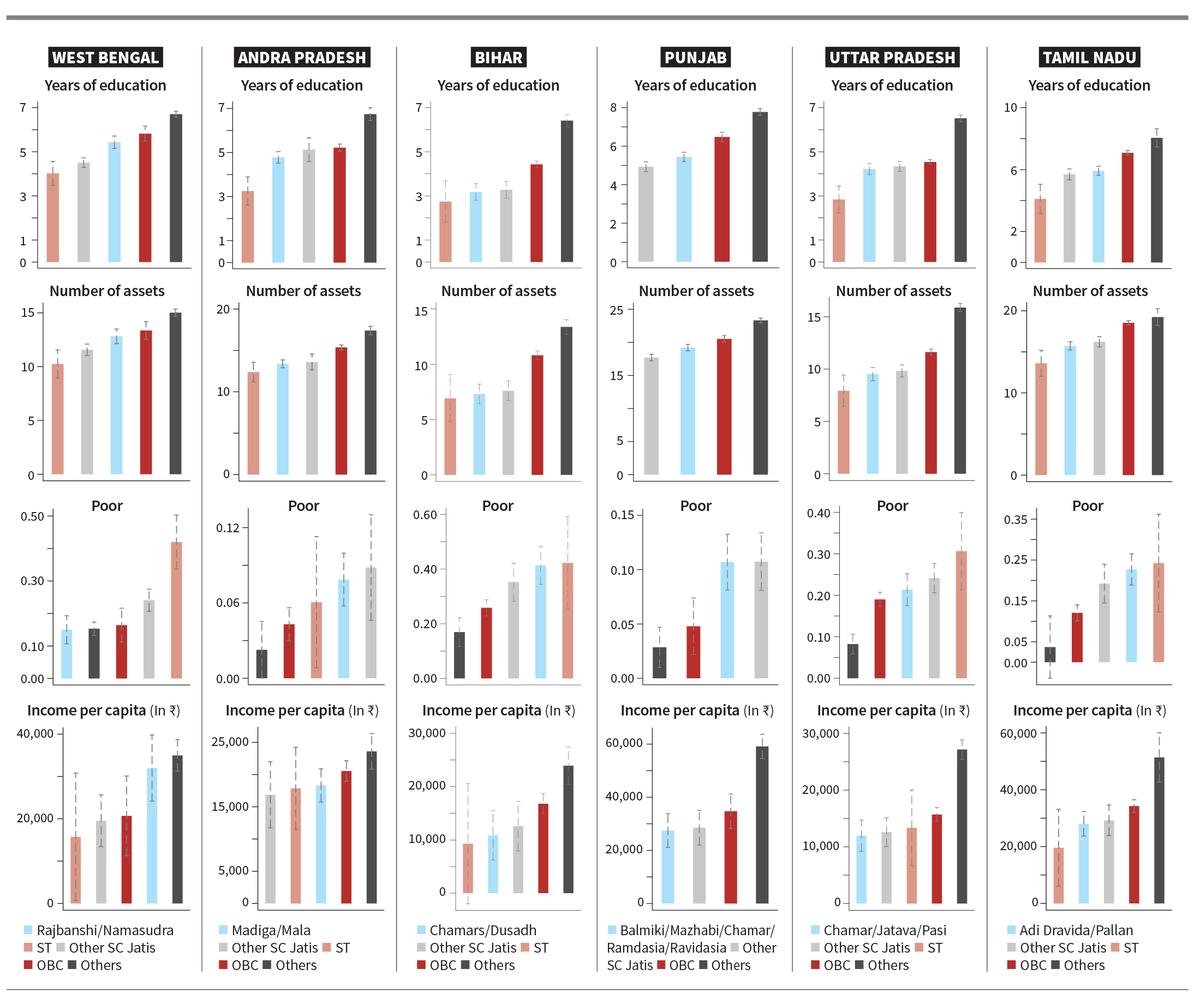

Here, we use data from six major States —Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal — and explore whether some SC castes have disproportionately benefited from reservations, leaving others behind.

What data from different States tell us

In Andhra Pradesh, our estimates reveal that while there are slight differences between the two major SC groups — Malas and Madigas — the disparities are not significant enough to warrant subdivision of the quota. By 2019, both groups had seen improvements in education and employment, and both were equally likely to benefit from white-collar jobs. A similar story emerges in Tamil Nadu, where the two largest SC groups — Adi Dravida and Pallan —were almost indistinguishable in terms of socio-economic outcomes by 2019. But other States paint a more complicated picture.

In Punjab, where the SC quota has been subdivided since 1975, the data suggests that this policy has led to better outcomes for more disadvantaged SC groups, such as the Mazhabi Sikhs and Balmikis. These groups, once marginalised even within the SC category, have begun to catch up to more advanced groups such as the Ad Dharmis and Ravidasis.

On the other hand, Bihar’s experiment with subdividing the SC quota into a “Mahadalit” category in 2007 is a cautionary tale. Initially designed to target the most marginalised SC groups, the policy eventually faltered as political pressure led to the inclusion of all SC groups in the Mahadalit category, effectively nullifying the purpose of the subdivision. The broader takeaway from these findings is that while there is some heterogeneity within the SC category, the disparities between SC groups and upper-caste groups (general category) remain far more pronounced. In other words, the gap between SCs and the privileged castes is still much larger than the gap between different SC subgroups.

Are reservations accessible?

We need good jati-wise data on actual use of reserved category positions. The closest we can get is based on a question from the India Human Development Survey (IHDS) that asks potential beneficiaries if they have a caste certificate — a prerequisite for accessing reserved positions in education and employment. These numbers can be seen as proxy for actual access in the absence of authoritative official data.

In States like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, less than 50% of SC households report having these certificates, meaning that a large portion of SCs are excluded from the benefits that are supposed to uplift them. Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh fare better, with over 60-70% of SC households holding caste certificates, but these States are the exception rather than the rule.

This highlights a fundamental problem with the current system — access. Without ensuring that all eligible SCs can actually benefit from reservations, subdividing the quota becomes a secondary concern. The focus should first be on improving access to reservations across the board, ensuring that those who are entitled to these benefits can avail them.

Is quota-within-quota the solution?

The idea of a ‘quota-within-quota’ is not without merit. In States like Punjab, where there is a clear disparity between SC subgroups, subdividing the quota has helped bring more disadvantaged groups into the fold. But this is not the case everywhere. In many States, like Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, the data suggests that there is little need for further subdivision, as the benefits of reservations are already being distributed fairly evenly across SC groups.

Moreover, the political motivations behind quota subdivision, as seen in Bihar, can often undermine the policy’s effectiveness. Decisions about who gets to be included in the most disadvantaged category are often driven by political expediency rather than empirical evidence. This dilutes the impact of affirmative action and risks turning the reservation system into a political tool rather than a genuine instrument for social justice.

Furthermore, the Supreme Court’s suggestion of introducing a “creamy layer” exclusion for SCs — similar to what is in place for Other Backward Classes — needs a stronger evidentiary basis.

The affirmative action policy consists of quotas as well as monetary benefits (scholarships or freeships, lower fees). The income criterion can be used to decide on eligibility for the monetary component to keep the monetary benefits for those who genuinely need it. However, there is no evidence that for historically stigmatised groups, improvement in class status necessarily reduces discrimination, whether it be in jobs or housing. Despite untouchability being abolished, covert and overt instances of untouchability persist. As elsewhere in the world, the stamp of a stigmatised social identity doesn’t disappear easily with economic mobility. Reservations have helped in creating a Dalit middle class, which over time can reduce stigma and gradually set the stage for creamy layer exclusion in the future. However, we are not there yet.

Finally, the urgent need for updated data cannot be overstated. India’s national Census, delayed for years, is the only source that can provide comprehensive data on caste-based disparities. Without this information, any attempt to reform the system will be based on incomplete/outdated evidence.

India’s reservation system has undeniably helped lift millions out of poverty and into the middle class, but it is far from perfect. As debates around ‘quota-within-quota’ policies continue, the focus should remain on improving access to affirmative action for all SCs and addressing the larger disparities between SCs and upper-caste groups. If carefully implemented, reservations can continue to be a powerful tool for social justice — but only if the system is based on robust data and genuine need, rather than political calculations.

Ashwini Deshpande is with Ashoka University and Rajesh Ramachandran is with Monash University. Views expressed are personal.

Published – November 05, 2024 08:30 am IST