On the night of November 26, a sizable crowd gathered to observe an all-night candlelight vigil on Shanghai’s Urumqi Middle Road, named after the Uyghur city of Urumqi in the troubled northwestern province of Xinjiang. The road, one of Shanghai’s busiest and located in the city’s elite Xuhui and Jinganqu districts, had never seen an anti-government protest before.

The protest — it is not yet clear if it was spontaneous or coordinated — was triggered by a fire accident on November 24 in a highrise in a residential area in Urumqi. Ten people had died and nine were seriously injured, and pictures on social media appeared to show residents trapped in the fire as a strict Covid-19 lockdown delayed the arrival of rescuers.

The following evening, crowds spilt out in the streets of Urumqi, raising slogans demanding an end to the lockdown. The whole of Xinjiang had been under continuous lockdown for about 100 days. While people in most parts of China are weary after three long years of restrictions on movement and frequent coronavirus testing, in restive Urumqi, the fire and deaths served as a potent trigger for protests.

For several years, the majority Muslim Uyghur population of Xinjiang has borne the brunt of a brutal crackdown by the government seeking to force them to assimilate more closely with the ethnically and linguistically different mainland Chinese. In fact, some analysts believe that more than Covid, the ongoing lockdown in the province is intended to serve a political purpose.

Within hours of the protests in Urumqi, hundreds of Uyghur activists gathered in front of the Chinese consulate in Istanbul, Turkey, demanding to know why fire trucks were not allowed to reach the building and fire stairs were not allowed to be deployed.

The outrage, seemingly fanned by pictures of the burning building on Chinese social media, soon spread to 18 cities in China including Shanghai, Beijing, and Wuhan, and to the majority Han Chinese who otherwise have little in common with the Uyghur people.

***

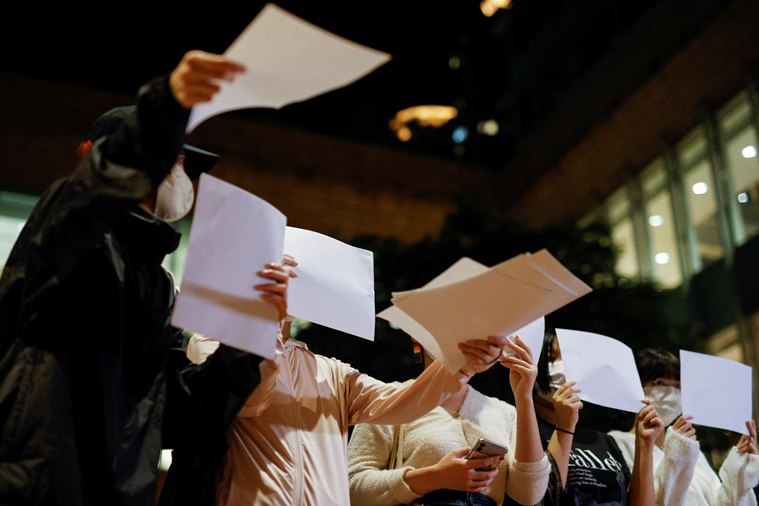

Global media have sought to paint the protests, especially those taking place on or around prestigious Chinese university campuses, as popular outbursts of anti-lockdown and anti-Zero-Covid sentiment. It has been suggested that President Xi Jinping may be losing the political gamble of forcefully implementing his “dynamic zero” policy (qingling). Indeed, slogans of “Xi Jinping step down” and “Communist Party step down” were heard even in the president’s alma mater, Beijing’s Tsinghua University.

Chinese media, on the other hand, have been largely silent about the protests. China’s English language media have cited a few commentators to accuse Western countries and media of being instinctively critical of the Chinese government, and of comparing every public protest to a potential “colour revolution”.

Unlike some of the Western commentary, accessible debates on Chinese social media do not see the protests as being either “popular” or “lasting”. And following heavy deployment of the Chinese Peoples’ Armed Police, accompanied by the use of artificial intelligence and cyber vigilance, and some arrests in Hangzhou and Shanghai, the protests seem to be petering out.

***

The seeming anti-Zero-Covid unrest was preceded by protests such as the one by thousands of workers at the Foxconn sweatshop in Zhengzhou, who protested against their horrific living conditions and the denial of over two months’ pay. In September, there were protests, accompanied by slogans of “no lockdowns” and “no frequent Covid testing” after a bus taking people to a quarantine centre in southwestern China crashed, killing 27 passengers.

The unrest manifested in the protests at the Foxconn factory, or after the Urumqi fire or the September bus accident, points towards the failure of the economic and social policies of the Communist Party. Indeed, China has been in the throes of a serious social and political crisis for decades. The insensitivity and indifference of the Party towards millions in the marginalised sections — rural migrant workers, the poor in the countryside, low- or no-wage urban labour — have been amplified by the suffering caused by the economic impacts of Zero-Covid.

In his work-report speech at the 20th National Congress of the CPC, General Secretary Xi sought to present an image of social stability and universal contentment in the country, and said his Zero-Covid policy is premised on the principle of “saving people’s lives”. While state media has been harping on the doubling of China’s GDP during the 10-year rule of Xi, there has been no mention of the rural migrant workers (nongmingong), whose numbers have increased from 256 million in 2012 to 376 million today. Xi’s 25,000-word report did not refer to them, and neither the state of Party has announced measures to help them cope with the impact of Zero-Covid.

***

Within the CPC, a factional struggle is being fought along ideological lines. There is a group that believes that “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics” is a fallacy, aimed at misleading the people into believing that the CPC’s leadership is committed to building socialism. Indeed, media reports have pointed out that among the slogans and demands, protesting students on Beijing campuses were heard singing the CPC anthem, The Internationale.

A young Chinese professor of history at one of Shanghai’s prestigious universities recently argued in an article that younger Chinese today are no longer inspired by China’s brand of capitalism. “Young Chinese are in the midst of a major reappraisal of their country’s modern history, one that is reshaping their attitudes toward the so-called socialist period, roughly defined as the years between the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 and the start of reform and opening-up in 1979,” (emphasis added) the historian wrote.

The government’s silence on the protests points to a possible further relaxing of Covid restrictions. Media in Hong Kong and Singapore have been reporting on “protests hastening Beijing’s exit from Zero-Covid”. It is well known now that the CPC had resolved to switch from Zero-Covid to “living with Covid” soon after the 20th Party Congress, but was thrown by an unexpected new Omicron surge. Even so, China’s National Health Commission announced “20 Measures” curtailing every aspect of Zero-Covid at a time when daily new cases were touching all-time highs in mid-November.

In a situation where the state has not bothered for months to expedite vaccination programmes, especially boosters for over 50 million elderly between the ages of 60 and 80, some health experts fear negative health impacts of the lifting of Zero-Covid restrictions in the coming weeks and months. That could conceivably trigger public and even “popular” protests as a new normal. It remains to be seen whether the authoritarian state will then respond with the heavy hand that it has so far refrained from employing.

Dr Hemant Adlakha teaches Chinese at JNU, and is Vice-Chairperson and Honorary Fellow at the Institute of Chinese Studies, Delhi. His most recent publications include ‘Confucius’ in Encyclopaedia of Race and Racism, 2nd Edition, and a chapter titled ‘Simla, McMahon Line, and South Tibet: Debates in China on Losing Territory to India’, in Boundaries and Borderlands: A Century after the 1914 Simla Convention.