Reassuring results from a large U.S.-based study show that patients with inherited pathogenic variants (PVs) in the cancer-related genes ATM, CHEK2, or PALB2 are no more likely to die from breast, colorectal, or pancreatic cancer than the average genetically tested patient with their cancer type.

The findings could be used to “inform clinical discussions about prognosis,” wrote Christine Veenstra MD, MSHP, associate professor of hematology/oncology at the University of Michigan, Department of Medicine, and co-authors in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

They explained that germline genetic testing is becoming increasingly important for cancer management because it is used to detect inherited PVs that can shape cancer treatment, surveillance, and testing of relatives.

Three genes in which PVs are often detected during germline testing are ATM, increasing risks for breast, pancreatic, and potentially colorectal cancers; CHEK2, increasing risk for breast and potentially other cancers; and PALB2, increasing risks for breast, pancreatic, and potentially other cancers.

Together PVs in these three genes account for approximately 3% of breast cancer cases and represent almost half of clinically meaningful PVs detected on germline testing. However, little is known about how ATM, CHEK2, or PALB2 PVs impact cancer mortality.

“As more patients with cancer undergo genetic testing, it is extremely important for patients and their clinicians to understand what the test results mean,” Veenstra told Inside Precision Medicine. “Patients want to know if their test results will change the chance that they will die from their cancer, and their clinicians need to know how to counsel them about this issue.”

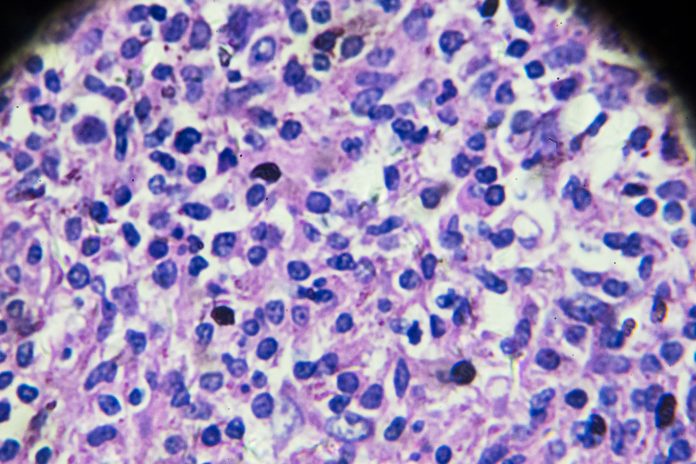

To address this, Veenstra and team used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results programs in Georgia and California to study cancer-specific mortality in nearly 80,000 adults diagnosed in 2013–2019 with breast (n=70,272), colorectal (n=5,822), or pancreatic (n=1,861) cancer.

All participants had undergone germline genetic testing at one of four specific laboratories. The study team developed a partnership with these laboratories, which meant that test results and specific PVs could be aggregated with patient outcomes in what they have termed the SEER-GeneLINK dataset.

Extensive statistical analysis showed that, during a mean 3.9 years of follow-up, individuals carrying ATM, CHEK2, or PALB2 PVs had no significant differences in breast, colorectal, or pancreatic cancer mortality relative to the average hazard across all genetically tested patients with that diagnosis.

Veenstra said this encouraging finding “does not suggest a need for different treatment strategies for these patients.”

The only PVs that conferred a risk that differed from the average were in BRCA1/2, where the risk for triple-negative breast cancer mortality was a significant 30% below average, and Lynch syndrome genes, which conferred a 30% lower risk for colorectal cancer mortality.

“For BRCA1/2 PVs, this [reduced risk] is attributed to chemosensitivity, initially thought to be platinum-specific, but shown in the INFORM trial to encompass doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide,” the study authors noted. “For Lynch syndrome, this has been attributed to superior tumor-associated immune response.”

A potential limitation of the study could be the short follow-up time.

“While we don’t expect the results to change significantly over time, a longer follow-up would be helpful especially for cancers that can recur decades after diagnosis, such as hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer,” said Veenstra. “We hope to be able to examine this in the SEER-GeneLINK dataset after a longer follow-up time.”

Creation of the unique dataset was an important part of the study. “There isn’t another dataset like this that exists,” Veenstra remarked. “It’s allowed interesting and clinically relevant studies like this to be done.”

She added that the data will also ensure that further analyses can be carried out as more cancer-linked mutations are discovered. “One of the benefits of the SEER-GeneLINK dataset, which is the most complete population-based sample of patients who have had genetic testing that exists to date, is that it allows us to apply these methods to other gene mutations across different cancer types. That work is underway.”

![Best Weight Loss Supplements [2022-23] New Reports!](https://technologytangle.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/p1-1170962-1670840878.png)