A new study from Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine reveals that biological age—reflecting the cumulative impact of genetics, lifestyle, and environment—may predict the risk of developing early colorectal cancer. Published in Cancer Prevention Research, the findings highlight accelerated aging as a key risk factor for colon polyps, a precursor to colorectal cancer, and suggest targeted early screening for those aging faster than their chronological age.

Unlike chronological age, which counts the years lived, biological age measures physiological changes at the cellular level, offering a more precise view of an individual’s health. “Biological age is an interesting concept, and it leads to the idea of accelerated aging, when your biological age exceeds your chronological age,” explained Shria Kumar, MD, the study’s senior author and a clinical epidemiologist and gastroenterologist at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. For instance, a person who is 50 but has a biological age of 55 experiences five years of accelerated aging.

The study’s findings are especially significant against the backdrop of rising colorectal cancer rates in people under 50. Early-onset colorectal cancer rates have been increasing by about two percent annually since 2011, according to the American Cancer Society. While current guidelines recommend beginning colorectal cancer screening at age 45, Kumar pointed out that this threshold might not sufficiently address the risk, as half of early-onset cases occur in individuals younger than 45.

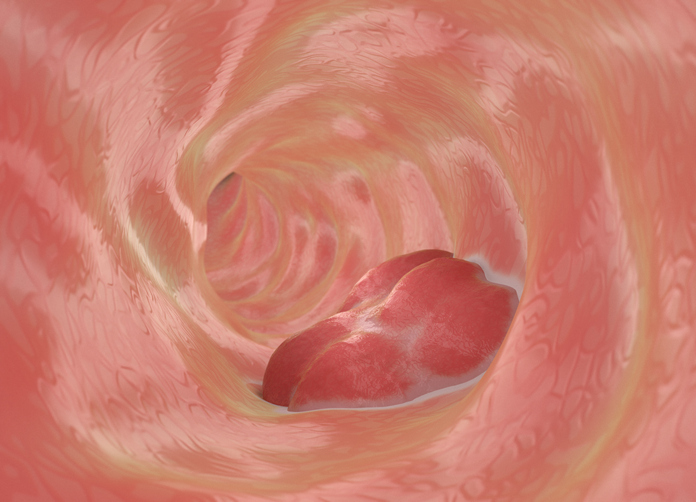

Researchers assessed the biological age of patients under 50 undergoing colonoscopies by analyzing their DNA. They found that each year of accelerated aging correlated with a 16% higher risk of developing polyps. Interestingly, while lifestyle factors like obesity and smoking were not directly linked to polyp risk in this study, they remain associated with accelerated biological aging.

“While I think the biological age finding is interesting and, maybe, exciting, the strongest risk factor for having a pre-cancerous polyp remains male sex,” noted Kumar, emphasizing that further research is needed to explore why men face a higher risk of developing polyps. She added, “It is pretty striking that multiple studies, including ours, have found that biological age provides distinct health information, and that could help us prevent cancer.”

This study underscores the potential for integrating biological age into colorectal cancer prevention strategies. With tools like colonoscopy—the gold standard for detecting and removing polyps—targeting individuals with accelerated aging could enhance early detection and reduce cancer incidence. Kumar emphasized the need for practical risk models, stating, “If we can develop a practical model to really identify and target higher-risk people and put them through colonoscopy, we can prevent their cancers.”

While the findings are promising, larger studies are needed to validate biological age as a routine screening tool. “Aging is multifaceted, and we need larger studies to establish whether most people’s biological age is the same as their chronological age,” said Kumar.

![Best Weight Loss Supplements [2022-23] New Reports!](https://technologytangle.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/p1-1170962-1670840878.png)