China has made substantial investments in the African continent. The road symbolizes a shift in a key China-Africa relationship: over debt and infrastructure.

In the 2000s and 2010s, China’s state-backed banks lent African governments billions of dollars for roads, ports, or airports built by Chinese State-Owned-Enterprises (SOEs).

Some deals, as in Angola and Congo, linked repayment to extracting natural resources. State-backed lending has since dwindled as China seeks new funding models. The expressway’s tolls, which in theory should pay for the road, are an example.

Africans live globalized lives. Those who travel to work on Chinese-built roads may do so in Japanese minibusses decorated with images of players from European football leagues, ringing messages on American social media platforms.

They worry about rising prices, a global pandemic buttressing supply chains, and a Russian decision to invade Ukraine.

China: The Upcoming Superpower

In the background of this scenario, China is just one foreign influence among many. But it is seen differently.

In April, the survey The Economist commissioned from Premise, a pollster, asked Africans in seven countries, a mix of democracies and authoritarian states, which would be more powerful in a decade: China or America.

In all seven, the answer was China. Overwhelmingly, they also felt that China’s influence was favorable as well.

Last month, a Russian naval frigate and a helicopter took part in a joint maritime drill with Chinese warships codenamed ‘Joint Sea 2022’ in the East China Sea. Based on the annual cooperation schedule between the two militaries, the drill focused on the joint maintenance of maritime security. “All the courses involve operations that the Chinese navy might use in the future while coping with the maritime challenges and safeguarding regional peace and stability,” said Zhang Huiwu, a commander from the Chinese navy.

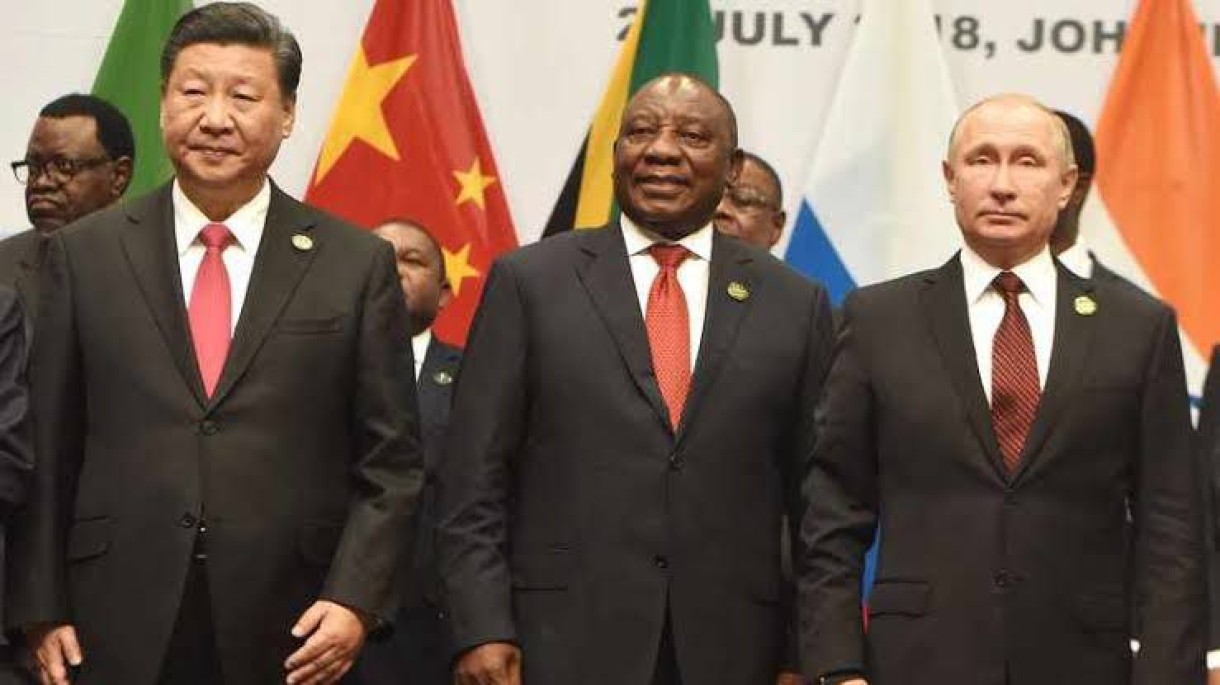

Driven by this imposing naval drill, defense analysts have said that South Africa will likely use China and Russia as “bargaining chips” in its dealings with the US after announcing a joint drill with the two countries in the Cape Route waters.

The drill is also seen as giving propaganda hype to Moscow after it announced that Russian forces had seized the small town of Soledar after months of reverses and heavy losses.

The joint exercises have started and have been codenamed “Mosi-2,” meaning smoke in the local Tswana language.

Earlier, this announcement came from South African military sources. “The Chinese and Russian navies would join its forces for the drill off the port city of Durban and Richard Bay, one of the strategically important shipping routes connecting Europe and Asia,” South Africa’s military stated. It will be the second such exercise after a previous drill in November 2019.

Russian warship Gorshkov armed with hypersonic cruise weapons will participate in the exercises. TASS agency reported the frigate is armed with Zircon missiles, which fly at nine times the speed of sound and have a range of more than 1,000km (620 miles), confirmed Al Jazeera on 23 January.

Experts believe South Africa is faced with a precariously failing domestic economy and needs financial support, which it might be able to get from the US. This is why some observers call the announced naval exercise a “political show” amid the ongoing confrontation between China, the US, and Russia.

The real question is whether these naval exercises will be able to help China and Russia gain any real military influence in the Indian Ocean. The coin has two sides, not one.

At home, the latest exercise has come under fire from South Africa’s main opposition party, the Democratic Alliance, which claims that by hosting the exercises, Pretoria has chosen sides.

“While our government has claimed to be neutral, this is just another of many incidents where the ruling party (ANC) has exposed their favoritism towards Russia and has done nothing but to showcase and prove the government’s lack of neutrality in this case,” according to the party’s shadow minister of defense and military affairs, Kobus Marais.

Pauline Bax of the International Crisis Group said the exercise coincides with the anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, “which is diplomatically quite awkward and something that South Africa could have pushed to another date.”

South Africa Is Not Joining The Anti-Russia Camp

Notwithstanding the opposition’s criticism, South Africa intends to send a clear message that it will not join the anti-Russia front and that Russia is not as isolated as the West would like.

Interestingly the Democracy Index 2022 published last month by the Economist Intelligence Unit states that two-thirds of the world’s population live in countries that are either neutral or Russia-leaning when it comes to the war in Ukraine.

Oriana Skylar, a Fellow at Stanford University’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies and the American Enterprise Institute, says that the upcoming naval exercises demonstrate “the potential for the presence of Russia-China cooperation in the Indian Ocean and how the two present a much greater threat to a continued US role and influence in the region than either would individually.”

The US would react in any case. On the invitation of the White House, forty-nine African leaders flew into Washington for the first continent-wide summit with the US in eight years as President Biden sought to use personal diplomacy to win back influence.

Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, at a panel with several African presidents, at the start of the three-day summit, charged the US rivals had a different approach.

He said China was expanding its footprints in Africa daily through its growing economic influence. He said Russia was “continuing to peddle cheap weapons” and deploying “mercenaries across the continent destabilizing Africa.”

Radio France International reports that President Biden plans to unveil $55 billion for Africa over three years. In one of the first announcements, the White House said the US would invest $4 billion by the 2025 fiscal year to train African health workers, a rising priority for Washington since the Covid–19 pandemic.

To sum up, Africa is on the verge of being sucked in by a phenomenon of international rivalry for gaining a foothold in the African continent that is still young in terms of natural resources and geographical location.