‘We could save Aakash because we treated him within the golden hour. Lipids are deposited along our blood vessels and with vigorous activity, the fat cluster may dislodge, travel to the brain and block the artery,’ says Dr Mukesh Sharma, Director of Neuro-intervention and Head of the Stroke Programme at CIMS Hospital, Ahmedabad

Thirty-five-year old Aakash Batra’s* world stopped at precisely 9.45 am on the third Friday in February. He was reviewing the day’s game with his tennis coach when he suddenly slurred, lost his speech and crumbled in a heap as he couldn’t move his right limbs. Within an hour, he was diagnosed with brain stroke at a local hospital in Ahmedabad, given clot-busting drugs and rushed to a bigger facility so that he didn’t miss the golden hour for survival. Today, he’s learning to talk again with some help from a speech and physical therapist. “Aakash can now form short sentences with three or four words although sometimes there is a problem of association. So he will end up saying ‘bottle’ when he means ‘water’,” says his wife Prarthana,* who has been the pillar that he now leans on.

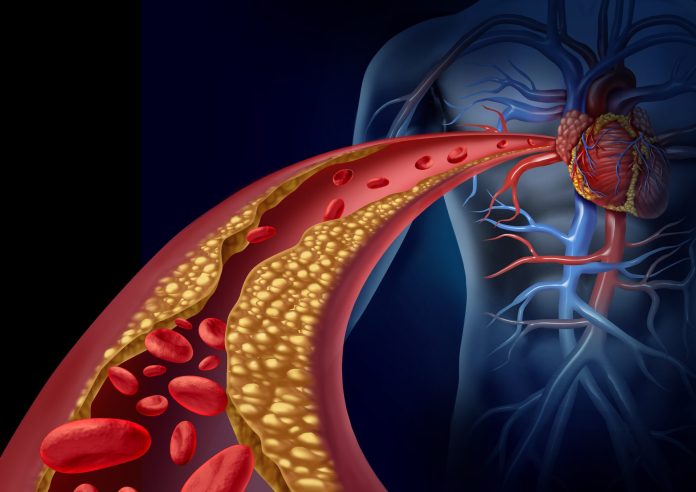

The words mean a lot to her, considering the complexity of his stroke meant that he could be immobilised forever. And although both Aakash and Prarthana run a healthcare company of their own, they were not aware about brain strokes and had nothing to go on. While such strokes are caused by blood clots, in Aakash the blockage was caused by a lipid or a fat deposit. Since time is of the essence in addressing the condition, the family rushed him to a local hospital where an MRI confirmed the presence of a clot. “He was attended to within 30-45 minutes of him showing symptoms. But in the absence of specialists, they gave him clot-busting drugs so that we could shift him to CIMS Hospital, Ahmedabad,” says Prarthana. Dr Mukesh Sharma, the director of neuro-intervention and head of the stroke programme at the hospital, was in for a surprise. This was probably the third time in his 15-year career that he saw a fat deposit clogging the brain artery. “This is very rare but possible. Lipids are deposited along our blood vessels and with vigorous activity, the fat cluster may dislodge, travel to the brain and block the artery. In his case, the plaque could have ruptured from the aorta in his heart, floated to the brain and got stuck there. Multiple factors, even viral infections, can damage the layer of plaque and dislodge it. In blood clots, the first line of treatment is dissolving drugs which must be given within an hour of the stroke. Aakash needed intervention,” says Dr Sharma. That’s when he did a mechanical thrombectomy, where specialists use endovascular devices to either break up the clot, dissolve or suck it out through a catheter-like vacuum.

Two days after the fat deposit was removed, Aakash had to undergo a craniotomy, where a bit of his skull was removed, to relieve the swelling in his brain. He was then shifted to the ICU where he spent nearly 10 days, even suffering seizures. Six weeks later, Aakash had to undergo cranioplasty, during which the portion of the skull that was removed was put back in place.

You have exhausted your

monthly limit of free stories.

To continue reading,

simply register or sign in

Subscribe to read on

Select your plan

All-Access

Access to premium stories

Digital Only

Access to premium stories

This premium article is free for now.

Register to continue reading this story.

This content is exclusive for our subscribers.

Subscribe to get unlimited access to The Indian Express exclusive and premium stories.

This content is exclusive for our subscribers.

Subscribe now to get unlimited access to The Indian Express exclusive and premium stories.

Dr Sharma says he could save Aakash because of the speed of treatment. “As soon as such patients arrive at a hospital, a ‘Code White’ is generated, which means prioritising the stroke-suspect patient for investigation, early admission, imaging and treatment. The stroke team, which comprises a neurologist, neuro-interventionist, radiologist, technicians of MRI and cath labs, assembles and decides whether clot-busting drugs would be sufficient or the patient needs to be taken to the cath lab,” he says.

However, this protocol is hardly adopted in tertiary systems in India, where there is also a lack of skilled manpower and specialists. Delay in triaging outside and inside hospitals remains a challenge for saving stroke victims, who need intervention within four-and-a-half hours of the onset of symptoms, known as the golden window. Less than one per cent of stroke patients in India get proper treatment within that period. According to the American Heart Association, every minute a stroke is untreated, the average patient loses 1.9 million neurons. With each hour left untreated, the brain loses as many neurons as it does in almost 3.6 years of normal ageing. This means a greater permanence of disability following a stroke.

A 2021 ICMR study — The Indian Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2019 — estimated that a stroke was the biggest reason for disability adjusted life years (DALYs) and a major trigger for deaths in neurological disorders. In 2019, the estimated number of strokes in India was about 1.29 million, deaths being 6,99,000. An absolute increase in stroke deaths by 36.7 per cent among younger adults has been observed in developing countries, compared to declining trends in developed countries. Nearly 30 per cent of all strokes occur in people aged less than 50 years and less than 10 per cent in those aged less than 40 years. A Ludhiana-based study done between 2010 and 2013 had calculated the rate of stroke incidence among young people (those aged 18-49 years) as 46 per lakh of population.

Dr Sharma spells out the cold facts. “Every minute, a person gets a stroke in India and every fourth minute, a person dies of it. While the developed nations are seeing a decline in the incidence of stroke, developing nations are seeing an increase, the triggers being our sedentary lifestyle, poor food habits, lack of sleep and exercise, addictions like smoking,” he says.

But Aakash didn’t have known risk factors. Says Prarthana, “He was physically very active, a tennis player since his teens, had no other comorbidities like high blood pressure, diabetes, cholesterol or a family history of disease. Till date we don’t know why it happened.” Aakash, who is still on his rehabilitation journey, could walk the day after he returned from hospital. However, his hand movements and speech were so badly impaired despite the swift intervention that he could not open his palm or hold objects. His memory was completely unaffected but he couldn’t articulate his thoughts through speech. “He’s getting there. Apart from physical therapy twice a day and speech therapy once a day, we engage him continuously as a family. We practise reading newspapers, giving him prompts, and that has shown results. He tries hard but there are days when he feels low. Then we call his friends home. He loved going out with friends after work and playing with his children. We take him to the office sometimes and attend meetings, just so that he remains spirited in his fight. Right now, he really wants to get back to driving his car and take the kids out on the bike,” says Prarthana. But she knows that patience is the synonym for a miracle.

(*names changed)

First published on: 11-06-2023 at 06:30 IST