Jonathan D. Grinstein, PhD, the North American Editor of Inside Precision Medicine, hosts a new series called Behind the Breakthroughs that features the people shaping the future of medicine. With each episode, Jonathan gives listeners access to their motivational tales and visions for this emerging, game-changing field.

One of the most remarkable patient stories of the 21st century has been that of Emily Whitehead—the first pediatric patient to receive chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR T) therapy. Emily’s parents have been along her side every step of the way, which is not something everyone can say. However, in the process, her father, Tom Whitehead, became incredibly moved by the experience with Emily and everything he saw. He decided to devote much of his time to helping families and patients who find themselves in Emily’s shoes. Today, Tom is doing that through the Emily Whitehead Foundation.

In this candid and emotional episode of Behind the Breakthroughs, Tom Whitehead shares intimate details of his journey by Emily’s side up to and through her treatment with CAR T, which occurred through a combination of serendipity and persistence. Tom also discusses in depth the challenges that patients and families face in dire medical situations, especially when it involves research-as-care.

This is the 2024 finale for Behind the Breakthroughs, and we will release our next episode on January 8, 2025.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

IPM: What was your experience with research-as-care during Emily’s journey?

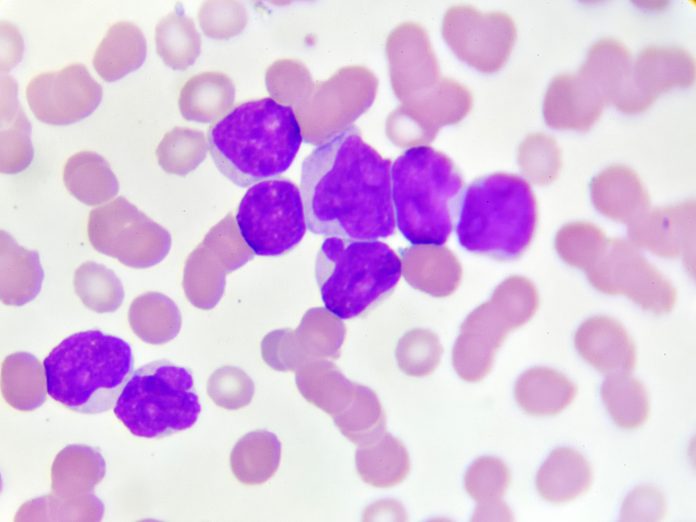

Whitehead: The day Emily was diagnosed with leukemia, all I knew about it was most of the people that I knew that got it didn’t make it. So, it was devastating to hear that she got cancer. We were told [acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)] is the kind of cancer you want to have if you have a child with cancer.

Emily was diagnosed on May 28th, 2010. June 11th, we’re taken into a room by the chief of surgery at the Penn State Hershey Children’s Hospital and told we might have to amputate Emily’s legs tonight—a tough start. She ended up in the intensive care unit (ICU). They did save her legs. However, we heard that throughout Emily’s treatment, this almost never happens. This seemed to be the case from the very beginning. It helped me learn how quickly your perspective can change. I was completely devastated on the first day walking down the cancer ward. Then we go to surgery to save her legs; she’s in the ICU, and within two weeks, we’re celebrating getting back to the cancer floor. However bad you think things are, they can always get a lot worse.

She got in remission in the first month, and the doctor said, “You guys had one of the toughest induction phases that we can remember, but maybe now things will smooth out.” It kind of did for a while. We would still hear, “Usually, by now, the kids have lost their hair from chemotherapy, and that doesn’t always happen.” That always made us wonder if it’s working. She stayed in that remission for 16 months, and then everything changed in October of 2011 when she relapsed for the first time.

Everything changed as soon as they said that chemotherapy almost always works for these children, and it’s very rare to relapse while still in treatment. But that day, they said, “You went from 85% to 9% chance of survival.” My wife got online and just filled out a second opinion form when we were down there within two days of finding out she had relapsed before we gave her any more medicine.

At that time, we set out to find a donor for a transplant. The goal was to go the first week of February of 2012. They found an unrelated donor who we had never met and were prepping her for a bone marrow transplant. Then, one day in January, they said, “Unfortunately, your donor isn’t available until the last week of February, so we have to put Emily on hold.” Then, in mid-February, she relapsed again, and they told us it was time to go home for hospice.

In between, we made a trip to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and turned down another clinical trial that wasn’t for leukemia. While there, they mentioned that the CAR T trial was ready, but they weren’t expecting to get approval to try for another three months.

While we were at Hershey waiting for the donor to show up, we started researching the adult who had been treated for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). So, when they said you’re going home for hospice, I paged them, and I told CHOP that I’m not taking her home; she’s not that sick looking, and we’re coming down for whatever you have. Dr. Susan Reingold said that the last email she read yesterday was that they got approval for CAR T, and it’s, you know, much quicker than we ever expected to have our internal review board (IRB) say it’s a go, and we think Emily would be the perfect patient. We were down to taking her home and enjoying the days you have left with her or trying this treatment. For me, it was a pretty easy decision.

Emily goes into a coma after she gets her CAR T cells and stays on the ventilator for 14 days. They tell us that there’s a one in a thousand chance she’ll be here in the morning. She makes it through all that and wakes up on her seventh birthday. I could hear the nurses in the hallway saying this is miraculous. But we got home and brought her home on June 1, 2012. We did 22 months of failed chemotherapy that failed her twice, and 23 days after she got her CAR T cells, she’s better. She went back to second grade that August after coming home June 1st.

IPM: What led you to found the Emily Whitehead Foundation (EWF)?

Whitehead: In December, the doctors got peer review and were allowed to talk about it. Emily’s picture was put on the cover of the New York Times. We had international media requests overnight. There were 7,000 readers every 15 seconds. With all of the media requests came calls from parents saying we were being sent home to hospice. I knew we could help. It’s hard to talk about that—I watched a lot of children die. After we started doing those interviews and got all that media attention, families called, and we just wanted to pay it forward.

We were trying to work with any foundations we could in the beginning, and some of those were using Emily’s story to raise money, and then maybe we’re not offering it to pediatrics. So we eventually said, “Okay, if we just use Emily’s name on our foundation and whatever money we collect, then we know where it’s going to go. It’s going to go towards these new advanced therapies and the research towards it.” That’s why we got started to make sure anybody who was going to use her name, that money would go back to these pediatric oncologists that are looking for new ways and help families get to the new treatments because I was talking to mothers in South America who are just sobbing because Emily’s treatment would save their kids, and they can’t get to it. They can’t even afford the visa to travel, and they’re begging us, like, “Come get my child and save my child, too.” That’s the kind of stuff that keeps you up at night.

But when I started helping people, I had times when I got calls from fathers who said, “You took my call six months ago, and it saved my child’s life.” I felt like it was the path we were put on and that I’m supposed to make a difference. We received this miracle in our family, and since then, we’ve been able to help families in more than 50 countries find hope in a trial since we started doing that.

Now, we spend most of our time advocating for the next patient. A lot of adults now, too, call and say, “My standard treatment is failing me; help me find a trial.” Our mission went from funding the research, and we’re switching it over to making sure these patients can find it. I’ve been told recently that I think less than 10% of the patients who could qualify for these new advanced therapies are getting them. We don’t tell them that we know that this trial will work for you. We try to help them find one, and at least we’re giving them hope rather than just going home or to hospice.

So, the media attention was overwhelming for us, but we turned it into a good thing where we spread awareness of what was going on.

IPM: So, nine out of ten people, it’s not working for them, not because the science or medicine isn’t working but because people can’t get to the treatment?

Whitehead: Or they choose not to. I think a big thing with the trials is adults feel like they’re going to leave a debt to their spouse or their estate, or they’re just afraid to go to a big clinical research center. Especially for people who don’t live in a city. They’re afraid to go to the city to begin with, and it just seems so overwhelming to them.

IPM: What was the hardest thing for you during Emily’s experience?

Whitehead: The worst thing I witnessed throughout all of that at every cancer center is that there are children fighting cancer alone. No one comes to see them. It’s heartbreaking. I would have never thought that would happen, but it does. There are some kids; the only people who see them are the volunteers, usually retirees who volunteer at the hospital.

IPM: What message would you like researchers and clinicians to take home from your experience with Emily?

Whitehead: I do share with people that more than one doctor told us that you’re just taking Emily down to Philadelphia to be a lab experiment, which is going to make her suffer more until she passes. I think there needs to be a better job of educating young doctors who are coming out. Many of them are doing rotations through where they’re treating CAR T patients.

IPM: How is Emily doing now?

Whitehead: Two Junes ago, Emily and I got to go scuba diving together in Mexico, and we filmed for an IMAX film called Superhuman Body: World of Medical Marvels to show Emily thriving today. I think why it got so much media attention is before Emily when you’d see a cancer survivor, especially an adult, the picture usually looked like they were still sick, and now when you see these kids that it’s working for, they’re thriving in life, you know, and I believe if you see Emily now, you didn’t know what happened to her; you can’t tell what happened to her. I think that kind of shift where people aren’t just looking to survive cancer anymore. They’re looking to thrive in life after and be back to normal.

Emily’s a straight-A student at the University of Pennsylvania. When we took her down to her dorm for freshman year last year, it was the first time she was away from us since she was in the hospital. She’s thriving in life, not just surviving, and she and I are now traveling all over. She’s joining me on stage to do keynote talks to share her story.

What we want everyone who’s listening to this in the industry to know is that we’re very thankful every day for all the hard work that they do and the extra hours they put in to save families like ours because they didn’t just save Emily; they saved our whole family. And in doing so, countless others may also benefit.

![Best Weight Loss Supplements [2022-23] New Reports!](https://technologytangle.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/p1-1170962-1670840878.png)