“Dear women, your identity is defined by your ability,” reads one of the several hand-written messages posted by students on a notice board. “Every child is a different kind of flower and together they make this world a beautiful garden…,” reads another post signed by “Rustam Walizada, Class-3”.

It’s 1 pm on a weekday at the Sayed Jamaluddin Afghan High School, the only such institution for children of Afghan refugees living in India. As children head to their classrooms, past the principal’s room, where a vertical tricolour flag of pre-Taliban Afghanistan is placed on a stand, the lunch-break din soon settles down.

Running out of a rented building on the cramped Masjid Lane in southeast Delhi’s residential colony of Bhogal, hundreds of kilometres from Afghanistan, where the ruling Taliban has suspended secondary and higher education for Afghanistan’s girls, the school is a rare safe space for Afghan children, especially girls.

Starved of funds after the Taliban came to power in Afghanistan in August 2021, the school, with 278 students from classes 1 to 12, was on the verge of shutting down before the Embassy of Afghanistan in Delhi reached out to India’s Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) for help.

India does not officially recognise the Afghanistan government though it engages with the Taliban through its embassy in Kabul. Afghanistan’s diplomatic missions, including its embassy in India, do so independently of the Taliban regime.

Sayed Ziaullah Hashimi, first secretary, Embassy of Islamic Republic of Afghanistan and a member of school board, says, “After the fall of Afghanistan on August 15, 2021, the school faced many difficulties. The situation was so dire that we had to vacate our premises because we had no money to pay rent. We couldn’t pay salaries to our teachers either. There was a possibility that school might have to be shut. That’s when India’s Ministry of External Affairs stepped in and promised to support us. Thanks to them, we have been able to continue to provide education to our students.”

Afghanistan’s diplomatic missions, including its embassy in India, do so independently of the Taliban regime. (Express Photo)

Afghanistan’s diplomatic missions, including its embassy in India, do so independently of the Taliban regime. (Express Photo)

While the MEA and school authorities refused to reveal details of the funds, sources said the school runs on a monthly budget of Rs 5.5 lakh.

The school was set up by the Women’s Federation of World Peace in 1994 as an educational centre for children of Afghan refugees in India. It grew into a primary school in 2008 and as a high school in 2017. It was then that the Afghan government led by president Ashraf Ghani, on a request from refugees in India, started funding the school.

“We are grateful for the support received from India to educate young Afghan boys and girls,” said Afghanistan’s Ambassador to India, Farid Mamundzay. “The fact that the school is still running has sent out two messages, loud and clear, to the Taliban. “One, nothing can stop the education of Afghan girls. Two, India has not left us alone in these hard times and has been a real friend by investing in the education of our children. In the past five years, we had to change school premises thrice but despite all the challenges, we haven’t given up.”

In October 2021, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, the school was forced to vacate its premises in Bhogal, and shift to a small flat, with classes mostly being held online.

“We tried to find a suitable place for the school or get some classrooms on rent but private schools did not agree to share their premises. Finally, in August 2022, we found this building in Bhogal which accommodates six classrooms. Due to a shortage of rooms, we are using the building for two shifts,” said Mamundzay.

Hashimi, the first secretary, proudly says that despite all these challenges, the school has reasons to cheer. For one, the Taliban’s ban has only emboldened Afghan girls in India to study — of the 278 students, there are more girls (143) than boys (135). “Also, 17 of our students who graduated in 2022 have made it to universities, including 13 in Delhi University. Seven of them are girls. The majority of our 35 teachers are women,” says Hashimi, walking through a corridor that has photos of “achievers” displayed on the walls.

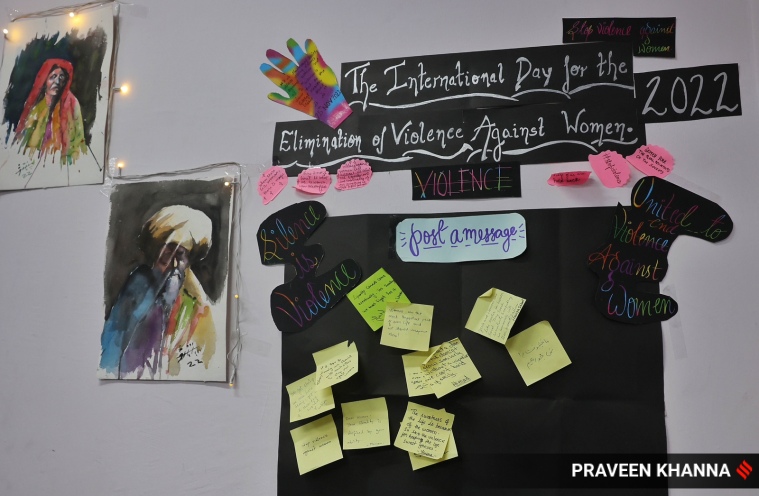

With lessons imparted in Dari and mixed classrooms with no gender segregation, the school offers an idyllic version of Afghanistan in the heart of Delhi. Besides English, Pashto and other science and humanities subjects, the school offers a course in Non-Violence and Gandhian Studies, besides teaching music, poetry, art and craft. While the school was earlier affiliated to the Afghan school education board, since the Taliban takeover, the certificates of the school’s Class 12 students are being stamped by the embassy in Delhi.

For the students –whose parents fled from Afghanistan in successive waves, some as recently as 2021, in the days before the Afghan takeover — their memories of “home” and Afghanistan are clouded by stories of repression.

Zohra Azizi, 16, from Panjshir province, came to Delhi with her mother in 2021, while her father stayed back to fight the Taliban. “I never met him after that. After the Taliban won, someone posted his photo on Facebook calling him a martyr and that’s how we got to know that he is no more,” says Zohra, breaking into tears. “My eight-year-old cousin, who studies in Class 3 in Afghanistan, told me that when she went to school to collect her report card, the Taliban told her not to come to school. All this has strengthened my resolve to study. This school and the education we are getting here means everything to me,” she says in Dari.

Nilab, 17, who moved to Delhi in 2017 after her brother was allegedly kidnapped and tortured for 45 days, says, “When I was in Grade 2, our school in Ghazni was bombed by the Taliban. Grenades were thrown inside… that scene still haunts me. All the news that comes from there is so sad that no one wants to go back. Girls in Afghanistan cannot celebrate birthdays, watch films or listen to songs like we do here. Why are they being deprived of all this,” she says.

The girls have the boys cheering them on. “In Afghanistan, girls are married off very young and they can’t study. I cannot express how bad I feel for them. Why are they doing this to the girls,” questions Ahmad, 16.

Nokhstin Ashrafi, 32, who teaches Dari in the school, says, “The Taliban is doing this to our women because they know that if a woman gets educated, an entire generation can’t be tamed. This school is our only ray of hope for refugee children.”

Kanishka Shahabi, the school principal, says, “Despite everything, we have tried to create a learning environment where the uncertainty of tomorrow’s future is overshadowed by today’s positivity. We hope India continues to support us and that we’ll soon get a permanent roof,” says

Talking of future plans, Hashmi says that they have set up a ‘Gandhi-Badshah Khan Educational Society’, named after Mahatma Gandhi and Abdul Ghaffar Khan, and they plan to get it registered soon. “We aim to make this a model school to be replicated in other countries where Afghan embassies are functional. We still have many issues to solve: our top priorities are finding a permanent building and getting registered with the CBSE,” says Hashimi.

![Best Weight Loss Supplements [2022-23] New Reports!](https://technologytangle.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/p1-1170962-1670840878.png)